A Tax-Smart Approach to Your Cost Basis

When it comes to calculating your capital gains tax, understanding cost basis is crucial. Essentially, the cost basis of an investment is what you paid for it. Determining capital gains when you sell an investment is just a matter of subtracting the cost basis from the sale price. It sounds simple enough, but calculating your cost basis can be complex—and if done incorrectly, you could end up paying the wrong amount in taxes.

Adjusting your cost basis

You can adjust your original purchase price for a variety of reasons. When you buy stocks, for example, you typically calculate the initial cost basis by adding commissions and fees to the per-share purchase price. The following are the most common reasons to adjust your investment’s cost basis:

- Commissions and fees: When you buy an investment, you can adjust the purchase price to include the transactions fees you were charged to acquire it. By doing so, you increase the cost basis of the asset, which reduces the taxable gain (or increases the deductible loss) when you choose to sell that investment.

- Reinvested dividends: The IRS treats reinvested dividends as if the money was distributed directly to you, meaning those payouts will be reported on a Form 1099-DIV and taxed as regular dividend income. Since those dividends have been taxed, the cost basis for the reinvested dividend is the price paid for the new shares, which increases your overall basis in that investment.

- Corporate actions: This normally includes mergers, spinoffs and stock splits. The total value of your investment won’t change most of the time, but the number of shares you have could increase or decrease, resulting in a change of the price per share.

- Wash sales: If you sell a stock for a loss but repurchase it (or a substantially identical security) within 30 days before or after the sale date, the wash sale rules will kick in and that loss will be disallowed. If you get caught by the wash sales rules, you can add that loss to the basis of the shares you repurchased.

Let’s look at an example: Imagine you invest $10,000 in a stock that pays out $200 in taxable dividends, which you automatically reinvest. That gives you an initial cost basis of $10,000 and an adjusted cost basis of $10,200. Now, imagine the value of your stock rises to $10,500 and you sell your holdings.

Using your original cost basis instead of the adjusted cost basis would result in a higher capital gain, and therefore a larger tax bill.

Know your accounting method

Another complication arises if you’ve purchased the same security on multiple occasions at a variety of prices.

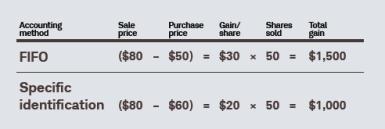

For example, say you buy 100 shares of a stock for $50 each, and a year later buy 100 more at $60 each. By the following year, the stock is trading at $80 and you sell 50 shares. Your capital gain will differ depending on which shares you sell. Let’s look at two common accounting methods that can be used to determine which shares are sold:

- First in, first out (FIFO) method: This is the IRS’s default accounting method. For partial sales, this method assumes you’re selling the oldest shares first, which can lead to a larger capital gain if the oldest shares have appreciated in value more than those acquired at later dates. In the example above, using the FIFO method would mean you’d sell the shares purchased at $50, resulting in a capital gain of $30 per share for a total taxable gain of $1,500 (see the chart below for more details).

- Specific identification method: This method allows you to identify which shares you want to sell. It is more flexible than FIFO and gives you the opportunity to optimize what gain or loss you must recognize. In your example above, you could choose to sell the shares purchased at $60, which would result in you only having to recognize a $20 per share gain for a total taxable gain of $1,000 (see the chart below for more details).

There are other accounting methods allowed by the IRS, so you may want to discuss your options with a tax professional before selling an investment.

Reporting your cost basis

Your brokerage firm lists the proceeds of sales in your taxable account on Form 1099-B. It may also report your adjusted cost basis, but this will depend on when you bought the assets. Policy reforms introduced after the financial crisis require banks and brokerages to report adjusted cost basis for:

- Stocks bought after 2010

- Mutual funds, ETFs and dividend reinvestment plans bought after 2011

- Other specified securities, including most fixed income securities, acquired after 2013

Whether your cost basis is reported to the IRS or not, you are ultimately responsible for the information on your tax return, so be sure to keep your original purchase and sale documentation to support your cost basis. For mutual funds, that includes statements showing automatic reinvestments.

You should also make sure your financial institution is using the accounting method of your choice. For example, at Schwab FIFO is the default method for stocks and ETFs, whereas the average cost method is the default for open-end mutual funds.

Using the reporting rules to your advantage

Usually, you want to minimize taxes by recognizing the smallest net gain (or largest loss) possible on your tax return. However, on occasion you might want to do the opposite. For example, you may decide to recognize a larger gain if you can offset it with a current loss or capital-loss carryover from a prior tax year, this is known as tax-gain harvesting.

Remember, it’s not what you make but what you keep after taxes that really counts. If you’re tax-smart about calculating and reporting the cost basis of your investments, you may be able to hold on to more of your return. Be sure to check with your tax advisor before entering into any transaction that may have significant tax consequences.

What You Can Do Next

Make sure that you’re considering the potential tax implications of your investments. Learn more about investment advice at Schwab.

Talk to a financial professional. Call Schwab at 800-355-2162, visit a branch, or find a consultant.

If your tax situation is complicated, you may want to consult a tax professional.

By

By