Should Muni Bond Investors Be Concerned About Climate Shocks?

Prior to Hurricane Laura making landfall in Louisiana and the wildfires in California and parts of the West igniting, the U.S. had already experienced 10 different billion-dollar natural disasters this year.1 The frequency and costs of major natural disasters have been rising over the past 40 years, and we think it’s a risk that municipal bond investors should pay attention to. Beyond the human toll, climate shocks have the potential to erode a municipality’s tax base, create economic disruptions, strain liquidity and impair assets, among other issues. We don’t believe that climate shocks pose a significant risk to the muni market as a whole, but they do pose a risk to some issuers—and that risk isn’t currently priced into the muni market, in our view.

While we don’t want to minimize the human toll, and we’re well aware that climate change has become a hot-button issue, municipal bond investors can’t ignore the fact that natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and droughts can have a major financial impact on the areas in which they occur. Leaving aside the question of why the pace of natural disasters has been accelerating, we will take a look below at how climate and weather disasters may affect issuers in the municipal bond market.

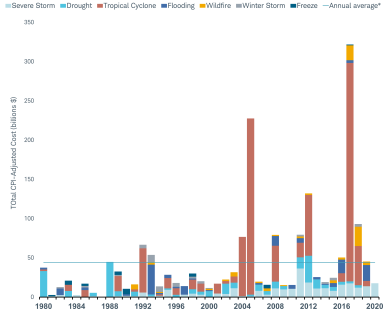

The number of natural disasters costing at least $1 billion has increased since 1980

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview” (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/). Data as of 07/08/2020.

Note: The annual average does not include 2020.

Disasters historically haven’t affected the broad market

Historically, most municipal issuers affected by natural disasters have been able to manage through the financial impact caused by the disaster. No state or local government rated by Moody’s Investors Service has defaulted on its bonds due to a natural disaster. However, downgrades are a possibility (when a bond is downgraded, its yield rises and its price generally falls).

Natural disasters don’t appear to pose a risk to the broad muni market either. We haven’t seen yields rise across the board following past natural disasters. Higher yields would mean that muni investors, on average, are more concerned about the increased risks—but historically, yields have been relatively unchanged following a major natural disaster.

The muni market has been resilient to past natural disasters

Source: Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index, as of 8/27/2020 and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview” (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/), as of 07/08/2020. Yield to worst is a measure of the lowest possible yield that can be received on a bond that fully operates within the terms of its contract without defaulting.

Smaller regional issuers are more at risk

Although climate shocks haven’t posed a past risk to the broad muni market or to large issuers like states, we believe they could pose a risk to some smaller regional issuers in the future. When a climate shock occurs, like a hurricane, flood, or drought, it can result in damaged infrastructure, economic disruption, and outmigration, among other issues. All of these could lead to lower revenues, increased expenses, or a combination of both. Issuers with smaller tax or revenue bases are more at risk compared to issuers with broad revenue bases, like states.

The muni market hasn’t priced in the risk of climate shocks, in our view

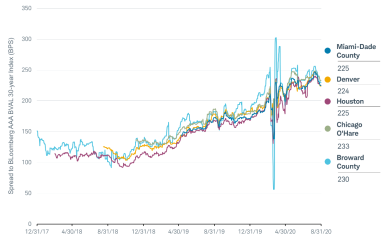

Yields for muni bonds don’t appear to incorporate the risk of climate change yet. To illustrate, we compared some similarly rated airport system revenue bonds, maturing close to 30 years from now. They were from Denver; Broward County, Fla., which is on the eastern coast of Florida and includes Fort Lauderdale; Miami; Houston; and Chicago. The risk of a climate shock, such as a hurricane or flooding, over the next 30 years is arguably much greater for Broward County, Miami, or Houston than for Denver or Chicago. However, yields for all bonds were nearly identical. In other words, investors weren’t getting higher yields for the potential risk of climate shock in this scenario (caveat: These are just a few examples in a market that has $3.6 trillion bonds outstanding).

Spreads for issuers more likely to be pressured by climate shocks are similar to issuers less likely to be affected

Source: Bloomberg, as of 8/31/2020. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only.

What to do now

We suggest the following steps for investors concerned about the impact climate change could have on municipalities:

1. Diversify by area.

When investing in individual bonds, we recommend holding at least 10 different issuers with differing credit risks. This includes issuers in different locations. As a reminder, we recommend that most investors in all states, other than New York and California, diversify nationally.

2. Choose areas that are less likely to be affected by climate changes and shocks.

It’s no surprise, but location matters. Areas like the Midwest are most likely to be affected by extreme heat whereas coastal areas are most likely to be affected by sea level rise. We don’t advocate avoiding issuers in these areas completely but be cognizant of the risks when you are looking at issuers there.

3. Focus on higher-rated issuers and do additional due diligence.

Historically, issuers with more financial flexibility—a quality that is often associated with higher credit ratings—have been better able to manage through the financial disruption of a climate shock. Muni issuers whose finances were already under pressure, which are usually already lower-rated, may be at risk of downgrades—and therefore price declines—because of the added strain. When a bond is downgraded, it reflects the opinion of the credit rating agency that the issuer has less financial flexibility to meet its debt service.

For example, before Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, New Orleans had already been struggling financially and was rated BBB+ by S&P—near the low end of the investment-grade spectrum. The storm devastated the city and caused massive damage from which the city took years to recover. Immediately following Hurricane Katrina, S&P placed the city of New Orleans general obligation (GO) bonds and several area issuers on credit watch in expectation of a decline in revenues. Approximately two months after Katrina, S&P downgraded many New Orleans issuers, including the GO debt, to B – which is considered “junk.” The credit rating for the city’s GO bonds has since recovered to AA-, but it took eight years to do so.

At the other end of the spectrum is Hurricane Sandy’s impact on New York City in 2012. Sandy was the fourth-costliest storm in U.S. history. Although there was substantial damage along the coastlines of New Jersey, New York, and other areas, there was little financial impact on New York City, the economic hub of the region. Due to the city’s already strong financial position, as indicated by its AA credit rating at the time, it could more easily respond to the negative impact from the storm. The city’s credit rating was unchanged following the storm.

4. Invest in issuers whose revenues are less impacted by climate shocks.

General obligation bonds, for example, tend to be backed by property or sales taxes and have historically been less financially impacted by climate shocks. Some revenue bonds, on the other hand, are more likely to be impacted by a climate shock. A revenue bond is a type of municipal bond issued by an entity that earns revenues from more business-like operations to pay their bonds back. An example would include a water and sewer facility, an airport, a college, or a not-for-profit hospital. Broadly speaking, we think that more business-like enterprises, like a health-care facility, airport, or toll road, are at a greater risk than a state government or local general obligation bond from the financial impacts caused by a natural disaster.

If the disaster causes a slowdown in economic activity, revenues could decline for issuers in the affected areas. For example, following Hurricane Katrina, S&P lowered the rating on Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport’s general airport revenue bonds to BB from A because of a “dramatic drop” in passenger traffic and uncertainty regarding future demand for airline travel in the area. The airport’s credit rating has since recovered and the bond are rated A- by S&P.

5. Choose shorter-term bonds.

Since Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico, the territory has lost roughly 4% of its population. Over time a declining population can result in a smaller tax base. Population trends often take years to develop so a focus on short-term munis can help reduce this risk. Be cautious with longer-term munis that are lower-rated and are in areas where climate shocks are probable.

Unfortunately climate shocks, like hurricanes, floods, and fires, are likely to continue. However, muni investors can take steps to lessen the risk on their portfolios. Investing in a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund that is well-diversified can help reduce the risk of a small number of issuers facing credit pressures due to a climate shock. Consequently, it most likely won’t have a large impact on the funds value. However, investors in individual bonds should take notice of the risks that climate shocks may pose as it’s generally hard to achieve adequate diversification for every dollar invested using individual bonds. For help selecting the right investments for your goals reach out to your local Schwab representative.

1 Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview” (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/). Data as of 07/08/2020.

What You Can Do Next

- Follow the Schwab Center for Financial Research on Twitter: @SchwabResearch.

- Talk to us about the services that are right for you. Call a Schwab Fixed Income Specialist at 877-566-7982, visit a branch, find a consultant or open an account online.

- Explore Schwab’s views on additional fixed income topics in Bond Insights.

By

By