Timing Matters: Understanding Sequence of Returns Risk

Experiencing a market drop in the early years of retirement can create problems that go beyond the immediate hit to your portfolio—potentially to the point where you permanently lose years’ worth of income. That could prove catastrophic if you’re just embarking on what could turn out to be 25- or 30-year retirement.

Timing matters

At issue here is a phenomenon known as sequence of returns risk. “Sequence” refers to the fact that the order and timing of poor investment returns can have a big impact on how long your retirement savings last.

After all, a retirement portfolio generally isn’t just a lump of cash in a savings account that you draw inexorably down to zero. It also includes a mix of investments that can provide both income and growth over time. Ideally, the growth will replenish at least a portion of what you take out, making your withdrawals more sustainable over the length of the retirement you’ve envisioned.

However, a major drop in the early years of retirement can scramble this picture. When you tap your portfolio as it’s losing value, you have to sell more investments to raise a set amount of cash. Not only does that drain your savings more quickly, but it also leaves you with fewer assets that can generate growth and returns during potential future recoveries.

In contrast, if a decline occurs later in your retirement, you may not need your portfolio to last as long or continue growing to fund a long retirement, so you may be in much better shape to fund withdrawals.

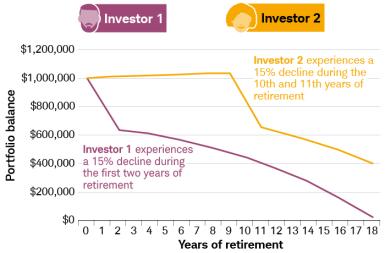

The chart below shows what happens to two investors who start with $1 million portfolios, take initial withdrawals of $50,000 (with 2% inflation adjustments each year after), but then experience a 15% drop in portfolio value. The investor who faces such a decline early in retirement runs out of money far sooner than an investor who does so later.

Troubled beginning

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research. This chart is hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. Both hypothetical investors had a starting balance of $1 million, took an initial withdrawal of $50,000, and increased withdrawals 2% annually to account for inflation. Investor 1’s portfolio assumes a negative 15% return for the first two years and a 6% return for years 3–18. Investor 2’s portfolio assumes a 6% return for the first nine years, a negative 15% return for years 10 and 11, and a 6% return for years 12–18. Does not reflect expenses, fees, or taxes.

“If the decline is steep or lasts awhile, that could make it even harder to recover,” says Rob Williams, managing director of financial planning, retirement income, and wealth management at the Schwab Center for Financial Research. “So, the question becomes: How can you help minimize the lost ground?”

Keep a reserve

One approach is to maintain a short-term reserve of low-risk liquid investments that you can use to cover your expenses while you avoid tapping your stocks.

Rob recommends keeping a year’s worth of expenses in cash investments, and another three to five years’ worth of expenses in high-quality short-term bonds and cash equivalents. With such a reserve in place, you might feel more comfortable about having a decent chunk of stocks on hand that can generate growth later.

Scaling back

If you don’t have a reserve or haven’t otherwise prepared, you may want to consider scaling back a planned withdrawal or even skipping it. You could also forgo inflation adjustments or postpone large expenses. In short, anything you can do to avoid selling investments when the market is down could potentially benefit your portfolio down the line.

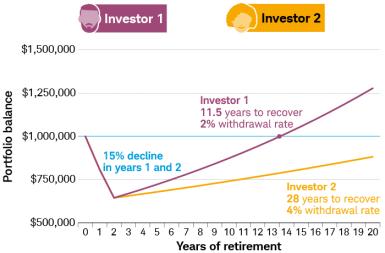

This chart shows what would happen to our two investors from above—with their $1 million portfolios and $50,000 initial withdrawals—if they took less from their portfolios after being hit by 15% drops in the first two years of retirement. Investor 1 opts for a 2% withdrawal rate, while Investor 2 takes out 4% a year, and they both return to 6% annual returns.

Headwinds

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research. Examples are hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. Both portfolios start with $1,000,000. Both portfolios experience 15% declines in years one and two, while both hypothetical investors also withdraw $50,000 per year. Starting in year three, both portfolios grow 6% a year. Investor 1 withdraws 2% a year. Investor 2 withdraws 4% a year.

A rebounding market should help them quickly make up lost ground, right? Unfortunately, no—those continuing withdrawals are a strong headwind. But by dialing back his annual withdrawals to 2%, Investor 1 will be back where he started after roughly 11.5 consecutive years of 6% annual gains. With a 4% withdrawal rate, Investor 2 would have to have 28 straight years of 6% gains to fully recover.

What You Can Do Next

We can help you with retirement income. Learn more.