Is China’s Bear Market an Opportunity?

Key Points

China’s stock market pullback this year has been in line with the average annual drawdown; historically, this volatility has tended to produce double-digit annualized gains.

The recent drop seems to be driven by a regulatory crackdown, not an economic slowdown, with the market not responding to the economic outlook, but to the policy uncertainty.

Regulatory reform may continue, but the market’s reaction may be overdone.

In the United States, the political process addressing issues of tech giant data becoming more of a public good, user privacy, and the labor impact of the tech-enabled gig economy is slow moving. But, in China, it can seem to come overnight.

In response to recent regulatory policy changes, Chinese stocks are in a bear market, as defined by falling more than 20% from its high. The slow slide in China’s stock market from its February peak sharply accelerated last week and spread beyond education and meal delivery stocks targeted by the latest regulatory crackdown. The stocks in the MSCI China Index plunged 14% in three trading days as the view changed from calmly interpreting regulators’ actions as only focused on a few big tech firms to alarm that no industry is isolated from a sudden rush of regulatory reforms. Investors in emerging markets have felt the drop, as China currently makes up one-third of the MSCI Emerging Market Index. This has left the MSCI Emerging Market Index flat year to date.

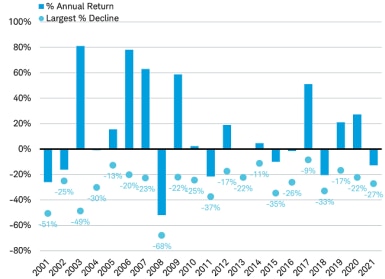

This outcome for investors isn’t new. Historically, investing in China’s stock market has come with high volatility—and high returns. This year, MSCI China Index has gone from being the strongest in the world, with a 20% gain year-to-date on February 17, to a year-to-date loss of -12% as of July 30, making it one of the world’s worst performers. This year’s peak to trough drawdown of -27% is in line with the -28% average annual drawdown over the past 20 years since China entered the World Trade Organization in 2001, as you can see in the chart below. Historically, investors have tended to be compensated for this heightened volatility with double-digit annualized total returns over the past 20 years (from 7/30/01 to 7/30/21 the MSCI China Index produced an annualized total return of 11%).

Annual performance of the MSCI China Index

Source: Charles Schwab, Factset data as of 7/31/2021. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Limited spillover

Investors often equate bear markets with economic recessions. But, for China, that isn’t usually the case. In fact, China’s economy is far from recession on a wide variety of measures produced both inside and outside of China’s borders. China’s purchasing managers index remains in expansion territory. South Korean exports to China have surged in recent months. U.S. companies’ second quarter earnings have cited strength in China, including Coca-Cola’s reporting of demand running ahead of 2019.

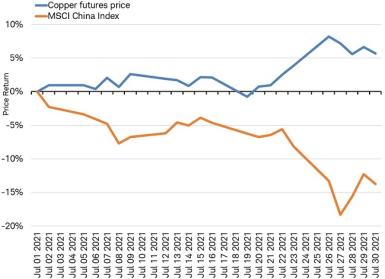

Copper, a commodity sensitive to China’s pace of growth—often called Dr. Copper due to its long history as an effective economic barometer—has gone up 6% even as China’s stocks fell sharply in July, as you can see in the chart below.

Dr. Copper sends solid signal on economy

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 8/1/2021. For illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Investors have seemingly discounted Chinese stocks due to heightened policy uncertainty, but do not appear to be downgrading the growth outlook for the world’s second largest economy. This likely puts some context around the limited impact on global markets; emerging market stocks ex-China are still up 8% this year.

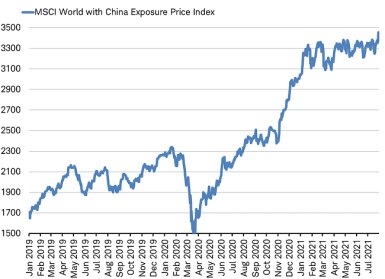

Furthermore, global stocks that have a large portion of revenue coming from China hit a new all-time high last week.

Global stocks with high sales exposure to China hit a new high last week

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 8/1/2021.

MSCI World with China Exposure Price USD Index aims to reflect the performance of companies with significant exposure to specific regions or countries, regardless of their domicile by deriving a company's economic exposure using the geographic distribution of its revenues. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses, and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

More to come?

If this year’s drop in China’s stocks is typical and tied to regulatory uncertainty instead of economic uncertainty—when will it end? To try to answer this question let’s take a quick look at some of the more notable regulatory actions.

- In November 2020, regulators pulled the Ant Financial IPO just days before the company was set to go public.

- In December 2020, regulators launched an anti-trust investigation against Alibaba, whose scope expanded to other Chinese tech firms.

- In March 2021, fines were issued to 12 different companies, including Baidu and Tencent, for insufficient review of the impact on competition of their previous acquisitions.

- In early July, Didi Global, the ride hailing app, was banned from registering new users just two days after its IPO on June 30.

These regulatory actions may have been intended as efforts to preserve the tech leaders’ role as national champions of innovation, but address what Chinese policymakers see as a source of social inequality and security risk. The anti-trust penalties targeted abuses of e-commerce market dominance. Restrictions on Ant focused on limiting shadow banking to better ensure financial security and stability, and those targeting Didi took aim at data security. Investors interpreted these as largely company-specific actions with little broad market impact, and China’s stock market held up well.

Until July 24th, when the Chinese government introduced new rules banning for-profit after-school tutoring of core subjects and called for meal-delivery companies to raise wages and benefits for their drivers.

These actions likely triggered the recent sell-off, as investors no longer saw China’s regulatory actions limited to tech giants, raising the uncertainty of what industry could be targeted next.

Yet, the intensity of the crackdown may soon fade. The latest regulatory actions appear tied to the census report released two months ago, which highlighted that China may not be making enough progress on its demographic problems. The actions against the for-profit education sector were meant to ease the financial burden on households; the high cost of child raising is the most often cited reason for China’s birth rate being so far below the replacement rate. Mandating that meal-delivery firms, like Meituan, raise wages and benefits for their drivers directly dealt with the persistent issue of income inequality. China’s official data estimates there are 200 million “gig workers,” making up about one-quarter of China’s entire labor force. However, the implementation of these regulatory responses to the report were likely delayed until late July, due to the 100th anniversary celebration for the Communist Party.

There could be more regulatory actions to follow the rollout discussed above. Housing and healthcare costs directly impact childrearing costs and worsen income inequality. It is possible property developers and healthcare companies may be potential targets of additional regulation. In our opinion, regulators would tread cautiously in these areas, perhaps by using price controls focusing on childbirth and low-income housing, rather than targeting destruction of these for-profit sectors. These mainstream ideas would not be new for China or elsewhere, suggesting less of a potential market response.

Bearing the bear

Longer-term investors in emerging market stocks may be able to bear this year’s bear market in China with some degree of comfort knowing that:

- The bear market is tied to near-term policy uncertainty, rather than a broader economic downturn that could linger.

- China’s stock market has already dropped in line with the annual average of about 30%.

- Other emerging markets have not followed along in the bear plunge.

Timing moves in any market is difficult and China can be even more challenging. There is risk that the regulatory rollout may continue, not to mention the potential for COVID-19 related concerns and the tense U.S.-China relationship to weigh on the growth outlook. Yet, the potential for the regulatory intensity to ease without leaving significant economic damage suggests balance of risks could be tilted to the upside from current levels. High volatility is why having a long-term perspective is especially important for emerging market investors. Long-term investors in emerging markets like China know that patience may be rewarded with strong gains.

Michelle Gibley, CFA®, Director of International Research, and Heather O’Leary, Senior Global Investment Research Analyst, contributed to this report.

What You Can Do Next

Follow Jeffrey Kleintop on Twitter: @JeffreyKleintop.

Explore Schwab’s views on other international topics.

Talk to us about the services that are right for you. Call us at 800-355-2162, visit a branch, find a consultant, or open an account online.

By

By