3 Mistakes to Avoid When Making a Large Portfolio Withdrawal

Imagine you've long dreamed of owning a vacation property, diligently saving for years. But to purchase it you need to make a large down payment and most of your assets are invested. Now that you're ready to make your dream a reality, how do you navigate such a large portfolio withdrawal?

Should you take the money out over time as you search in earnest for your second home or wait to withdraw it all at once? Which investments should you sell? How will the withdrawal affect your taxes? And what can you do to limit the possibility that the transaction will throw the rest of your portfolio off-balance?

"There's plenty of advice out there about how to save for your goals, but for many investors, there's less guidance or clarity regarding how to tap your investments once you reach a goal," says Rob Williams, managing director of financial planning, retirement income, and wealth management at the Schwab Center for Financial Research. As a result, many investors approach a sizable withdrawal the same way they would a smaller one, resulting in potentially negative consequences for both their taxes and overall portfolio performance.

Here are three of the most common mistakes people make when managing a large portfolio withdrawal—and how to avoid them.

1. Withdrawing it all at once

Selling substantial assets in a single calendar year—versus staggering the distribution over two or more years—increases your total taxable income and could bump you into a higher tax bracket.

"Depending on the size of the withdrawal, you might want to split it up over multiple years," says Hayden Adams, CPA, CFP®, director of tax and wealth management at the Schwab Center for Financial Research. "If you don't, you could get hit with a big tax bill."

To help minimize your taxes, start by figuring out how much money you'll need and how soon you'll need it, and work backward from there. Then you can look at several strategies, such as tax-gain harvesting or topping off tax brackets, to get the cash you need with the least amount of tax impact.

Here's an example. Let's say you and your spouse are both age 62 and want to come up with $50,000 to buy a second home in 2026. You plan to take the funds from your traditional IRA, meaning the withdrawal will be taxed as ordinary income. As a result, your total withdrawal will need to include the $50,000, plus whatever the resulting tax liability might be.

You expect to have $95,000 of regular income in 2025. Assuming you'll take the $31,500 standard deduction for a married couple come tax-filing season, your taxable income for the year would be $63,500, putting you in the 12% marginal tax bracket. What's the most tax-efficient way to tap your IRA?

Approach 1: Single withdrawal

If you took the full $50,000 this year, your total taxable income—comprising your regular income and the IRA distribution—would bump you into the next higher tax bracket of 22%.

As a result, you would need to come up with a total of about $59,814: $50,000 for the planned down payment, plus an additional $9,814 or so to cover your taxes, since part of the withdrawal would be taxed at 12% and part at 22%.1

Approach 2: Split withdrawal

If you split the $50,000 distribution over two years, you could stay in the lower 12% tax bracket (assuming no income or tax changes) both years, lowering your tax liability and putting less of a strain on your savings. It would work like this: In the first year, you would take $33,450 out of your IRA. The resulting tax at the 12% tax rate would be $4,014. Then, in the second year, you would withdraw $23,368, paying $2,804 in taxes at the 12% tax rate.2 All in, you would need to withdraw just $56,818 from your IRA and save $2,996 in taxes over two years.

Spreading a large withdrawal across several years, particularly if you're near the upper end of your tax bracket, can often result in a significant savings, Hayden says.

2. Avoiding losers

Investors often want to avoid selling investments at a loss, but it might make sense to target losers when you're looking for candidates to sell. "It's hard for many people to stomach losses, but selling losers can be a tax-smart move if those investments are in a taxable brokerage account," Rob says.

Not all underperforming assets are fit for the chopping block, but those with weak prospects or that no longer fit your investment strategy are prime candidates.

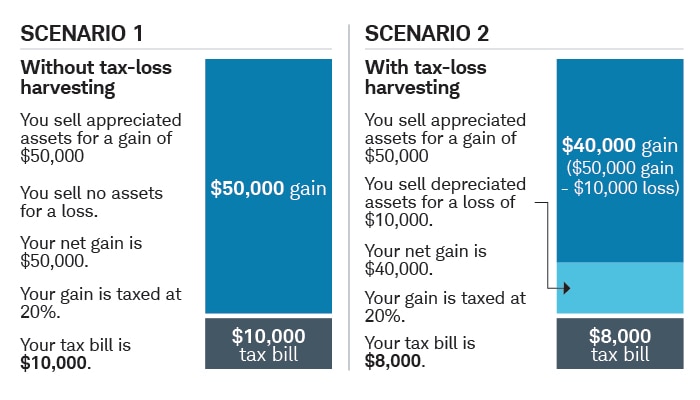

"When you sell an investment in your taxable account for less than you paid, you can use that loss to offset any gains you might have made from selling other appreciated assets," Hayden explains. This strategy is called tax-loss harvesting and can lower taxes on your investments if done wisely.

What's more, if your capital losses exceed your capital gains, you can potentially use those losses to reduce your ordinary taxable income by up to $3,000. Anything above that can be carried over to future tax years.

A large withdrawal is also an ideal opportunity to rebalance your portfolio. As withdrawals and market fluctuations alter the proportions of your portfolio holdings, your asset allocation may stray from its target, causing some positions to be overweight and others underweight. "It's important to keep your portfolio in line with your risk tolerance and time horizon," Rob says.

Cutting your losses can cut your tax bill

Offsetting capital gains with capital losses—a.k.a. tax-loss harvesting—can potentially lower your taxes.

Source: The Schwab Center for Financial Research

For illustrative purposes only. The long-term capital gains rate of 20% assumes a combined 15% federal rate and 5% state rate. Investors may pay higher or lower long-term capital gains rates based on their income and filing status.

3. Picking the wrong accounts

There's no rule that says you should use a single account when you need to come up with a large sum of money. In fact, it may make more sense to spread your withdrawals across several account types, in line with your tax plans and the overall composition of your portfolio.

Of course, this assumes that you've diversified your savings by tax treatment across tax-deferred accounts like a 401(k) or IRA, after-tax accounts like a Roth IRA, and taxable brokerage accounts.

"One of the features of tax diversification is that you can structure your withdrawals to minimize their tax impact," Hayden says. "Think of it as another way of filling up your tax bracket, but instead of spreading your withdrawal across multiple years, you're spreading it across multiple account types."

Recall that withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts are subject to ordinary income taxes, which can be taxed at federal rates of up to 37%. And if you tap these accounts prior to age 59½, the withdrawal may be subject to a 10% federal tax penalty (barring certain exceptions).

Distributions of assets held for over a year in a taxable brokerage account, on the other hand, may be subject to the lower long-term capital gains rates, which range from 0% to 20% (though higher earners may be subject to an additional 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax).

Meanwhile, withdrawals from Roth accounts aren't subject to any taxes, provided the account holder is over age 59½ and has held the account for five years or more since they first funded it. This isn't to suggest Roth accounts are always the go-to spot for big withdrawals, because you might not want to deplete these potentially valuable savings so quickly.

Rather, the question to ask before tapping any single account is whether you might find a tax-smart path to raising your desired sum by taking a bit from several different accounts. Taking portions from your tax-deferred, after-tax, and taxable accounts could give you the money you need, at the tax rate you desire, without knocking your portfolios out of balance.

When to consider borrowing

If you need access to capital but are hesitant to liquidate part of your portfolio because of tax consequences, such as a down market or other considerations, it might make sense to borrow to fund your goal.

If you were to borrow the funds at an interest rate that's less than your expected portfolio return, you could come out ahead. Of course, there is no guarantee your portfolio will achieve its stated objective, and you should consider whether you are willing to assume the risk that it won't.

If you borrow against your home, interest payments may be tax-deductible so long as you use the proceeds to improve your home or purchase a second home3 and your total itemized deduction is larger than your standard deduction. That can further reduce the cost of borrowing, subject to current limitations and caps from the IRS on how much you can deduct.

You could also consider borrowing against the value of your investments with a margin loan from a brokerage firm or with a securities-based line of credit offered by a bank. Both involve risk, and it's important to understand these risks before borrowing.4

Margin loans and bank-offered, security-based lines of credit might make sense for investors with higher wealth or flexibility who have low-volatility assets to borrow against, who are in control of their debt, and for whom the level of risk is appropriate. Entering into a securities-based line of credit and pledging securities as collateral involves risk if the value of your investments falls. Before you decide to apply for a security-based line of credit, make sure you understand the details, potential benefits, and risks.

Is a security-based line of credit right for you? Learn more about the Schwab Bank Pledged Asset Line®.

1Example assumes that the first $33,450 of distributions would be taxed at 12%, and any withdrawal amount over that would be taxed at 22%. This means an additional $26,364 withdrawal would be necessary for a total distribution of $59,814. The estimated tax of on this distribution would be $9,814, leaving $50,000 after taxes for the down payment.

2Example assumes a $33,450 distribution in year 1, followed by a $23,368 distribution in year 2, for a total withdrawal of $56,818 over 2 years. The total $56,818 withdrawal would be taxed at 12%, resulting in an estimated tax of $6,818, leaving $50,000 after taxes for the down payment.

3There is no deduction for interest paid on home equity loans and lines of credit, unless they are used to buy, build, or substantially improve the taxpayer's home that secures the loans. The law imposes a lower dollar limit on mortgages qualifying for the home mortgage interest deduction. Taxpayers may only deduct interest on $750,000 ($375,000 for a married taxpayer filing a separate return) of qualified residence loans. The limits apply to the combined amount of loans used to buy, build, or substantially improve the taxpayer's main home and second home.

4For a bank-offered, securities-based line of credit, the lending bank will generally require securities used as collateral to be held in a separate, pledged brokerage account held at a broker-dealer, which may be an affiliate of the bank. The bank, in its sole discretion, generally determines the eligible collateral criteria and the loan value of collateral.