8 Mistakes to Avoid When Planning for College Costs

Picture this: A family invests years of money, effort, and time so they can afford to send their kids to college, only for a mistaken assumption or planning error to cost them thousands. As plot twists go, this one is pretty common. That doesn't make it inevitable, though.

We've gathered some of the more common college-savings mistakes here—organized in loose chronological order relative to a child's college years—and listed steps you can take to avoid them.

Mistake #1: Waiting to save

When you start investing early, you give yourself time to potentially rack up more earnings in the form of capital gains, dividends, and interest—which can then go on to generate their own returns in turn, a dynamic known as compound growth. Every dollar you save in advance is one you won't have to draw from your income, loans, or other savings when it comes time to pay for college.

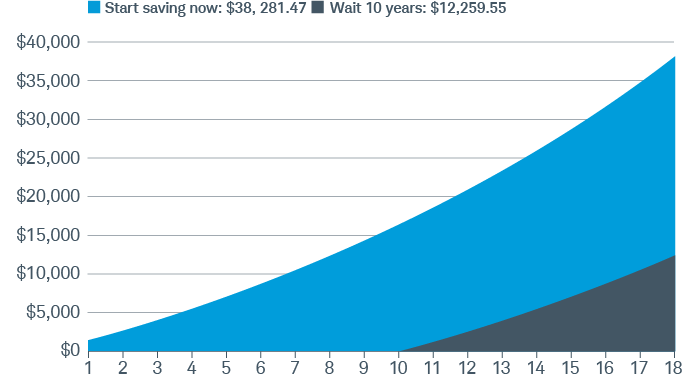

This chart shows what happens when you save $100 a month and earn a 6% return over 18 years versus what happens when you give yourself only eight years. The early mover ends up with more than $26,000 more.

The cost of delaying

Source: Schwabmoneywise.com. Assumptions: $100/month, 6% rate of return over a period of 8 and 18 years. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent a specific investment product. Dividends and interest are assumed to have been reinvested, and the example does not reflect the effects of taxes or fees. Each individual's situation may be different.

Action step: This is an easy one: Start early. Don't let procrastination be your enemy. Upon the birth or adoption of a child, open a tax-advantaged 529 college savings account and encourage family and friends to contribute to it. Then, keep the savings going with monthly, quarterly, or annual contributions, helping you harness the power of compounding to help you save for college. Tapping retirement savings to pay for a child's college should be the last resort, if at all.

Mistake #2: Pegging your savings target to the published cost of attendance

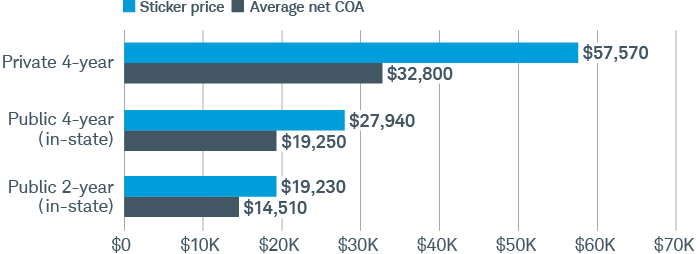

Colleges publish the cost of attendance (COA) to give families an approximate "sticker price" for tuition, fees, and room and board. However, this amount generally doesn't reflect the financial aid that many students receive. As a result, families could come away with the impression that they need to save a lot more than they do, potentially sapping their motivation to get started.

Sticker shock

Source: Collegeboard.org. 2022-2023 Published cost of attendance (COA) vs Net COA after grant aid (Figs CP-1, CP-8-10). Private schools refer to nonprofit institutions not for-profit. Net costs are after federal and state grants, scholarship, and tax benefits, which don't have to be repaid, and before student loans. Costs include tuition, room and board, books, supplies, transportation, loan fees and other expenses. For illustrative purposes only.

Action step: Look for the average net price of education. You can use resources like the National Center for Education Statistics' (NCES) College Navigator to get a better sense of what to expect. You might find that even seemingly expensive schools could be within reach.

Mistake #3: Trying to do it all with your savings

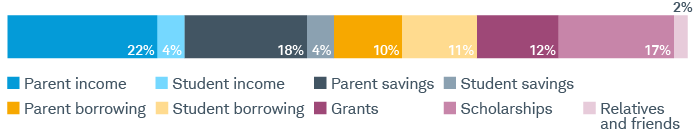

In the world of college planning, you might encounter an idea known as the "one-third rule." It says you should consider paying for one third of college costs with savings, one third with current income, and one third with loans (with appropriate adjustments according to your financial situation). You could also factor into students' own contributions, with some covering up to 20% of their own college costs (through a combination of income, savings, and loans).

Footing the bill

Source: Salliemae.com, How America Pays for College 2023, as of the academic year July 1, 2022 to June 20, 2023. For illustrative purposes only.

Action step: Decide what combination of income, savings, and loans makes sense for you and your family. Be sure to adjust your plans as your student grows into a young adult. A part-time job or summer employment could help them cover some of their bills.

Mistake #4: Assuming your accumulated wealth will hurt your chances of getting financial aid

Your assets may have a smaller impact than you might expect. The new student aid index (SAI)—basically, a scoring system reflecting a student's eligibility for financial aid based on the information provided via the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA)—considers up to only 5.64% of your non-retirement assets (such as checking, savings, brokerage accounts, and 529s owned by you for that student) when determining federal aid eligibility. Some assets—such as retirement accounts (401 (k)s, 403(b)s, 457s, or IRAs), the family's primary residence, or life insurance—don't count toward the SAI.

No matter your wealth, it's always worthwhile to fill out a FAFSA. While your income and assets may turn out to be too high for a needs-based grant, you may still need to complete a FAFSA to secure merit-based aid that some schools offer to high-achievers. Completing a FAFSA is also necessary step in securing federal loans.

Action step: Don't skimp on your retirement savings because you're worried they'll count against your future college student. Continue to save and invest, preferably through tax-deferred accounts, to potentially grow your retirement assets. Regardless of whether the student goes to college, retirement should be the top priority for parents.

Mistake #5: Putting too many assets under the student's name

Students' assets are weighted a little more heavily: Up to 20% of the student's non-retirement assets (such as a 529 owned by the student, custodial bank, or brokerage account) are considered available for college expenses when it comes to federal financial aid. As a result, the more non-retirement assets the student has in their name, the larger the burden of paying for college costs.

Action step: Consider a custodial 529. Although the assets are ultimately owned by the child, the SAI treats them as if they belonged to the parents. You can also enlist the grandparents by having them set up a grandparent-owned 529. These accounts won't be included in the SAI as of the 2024-2025 school year.

For wealthy families who don't qualify for federal need-based student aid, a custodial account may still make sense for gifting assets and to gain more favorable taxation on interest or dividend income via the kiddie tax rules.

Mistake #6: Trying too hard to lower your income late in the college-planning phase

Student aid eligibility is determined in large part by the parents' (and students') adjusted gross income (AGI), which is total income minus things like pre-tax retirement plan contributions. Up to 47% of parent's income (and up to 50% of the student's income) is factored into the SAI.

While parents have a few options for reducing their wages (such as saving more in a 401(k), 403(b), or 457) late in the college planning phase, the potential returns of a lower income diminish sharply once you go above an AGI of about $100,000–$125,000 for a family with two parents. So, it may not be worth it to defer income beyond a certain point.

Here's an example based on our research of the SAI and some COA figures: A family of four (two parents and two children) with an AGI of $50,000 could qualify for federal aid at almost any of the four categories of schools (I.e., public two-year, public four-year, private four-year average, and private four-year expensive), as long as their investment assets are below $400,000. A family of four with an AGI of $250,000 would likely have fewer options, probably confined to the more expensive tier of private schools, and then only if they had less than $50,000 of non-retirement assets.

Action step: Be realistic about how much income you can defer. You also need to decide how willing you are to lower your living standard for four-plus years. Cost-conscious wealthy families can focus on lower-cost, in-state schools or private colleges that offer aid based on non-financial factors. Such private colleges are often smaller and may not have the name recognition of a flagship university, but they may be willing to offer students larger aid packages to help increase their population, prestige, donor base, etc.

Mistake #7: Assuming that financial aid packages will cover any remaining costs beyond the family's expected contribution

Grants and full-ride scholarships are great but rare. Aid is more likely to come in the form of loans to students and/or parents. Families should carefully review their financial aid award package to see if they'll need to consider private student loans, part-time work, installment payments, or potentially a different school.

Action step: When deciding on a college, compare financial aid packages by splitting the aid between what does and doesn't need to be repaid. If the aid package isn't clear about what needs to be borrowed and who is responsible for repayment, ask the admissions office or financial aid office. Depending on the school, parents may also be able to negotiate for more financial aid.

Mistake #8: Choosing a college that is a "bad" financial fit

Some debt is expected, but loading up on too much, even for your child's dream school, can bury you. Some parents delay home purchases or even retirement because of student loan debt. Any time you need to borrow to accomplish a goal, make sure your debt is manageable.

Action step: When it comes to college, you should factor any future debt into your decision process from the beginning. Don't wait until the bills start showing up after graduation. More debt-averse families should consider focusing on saving or choosing schools that can offer more in grants and scholarships.

If you want to know whether a degree from a particular school is "worth it" relative to the potential debt you'd have to take on, you can look it up using the Education Department's College Scorecard website. You'll find graduates' median earnings 10 years after starting their education, which can give you a sense of whether a given debt load may be bearable. With a bit of research, you might a find a comparable degree for less cost and less debt.

If your student isn't clear on what they want to get out of college, consider a lower-cost school for the first couple of years. They can always transfer to a more prestigious or expensive college to finish their degree. Parents should also consider whether any parent-based loans (e.g., PLUS loans) can be managed without sacrificing their retirement and other goals.

Bottom line

Although financial aid has brought the opportunity for a higher education within reach of almost everyone, it's still worth it to plan ahead, preferably with some input from a financial professional or wealth planner.