4 Reasons to Sell Your Losers

We all experience losses in our portfolios, whether because of a market downturn or just lackluster performance. Fortunately, losing investments can have a silver lining. Through tax-loss harvesting, you may be able to use them to lower your tax liability and better position your portfolio.

Here are four situations in which it might make sense to sell your losers—and what to consider if you plan to reinvest the proceeds.

1. You want to realize some gains

When people talk about the benefits of tax-loss harvesting, it's often in reference to offsetting taxable gains elsewhere in their portfolio.

After all, even when the market has had a good run, lifting your holdings, you might still have some stocks that are below where you bought them. If you're looking to lock in some of those gains (aka tax gain harvesting), selling some of your losers can help minimize your capital gains taxes.

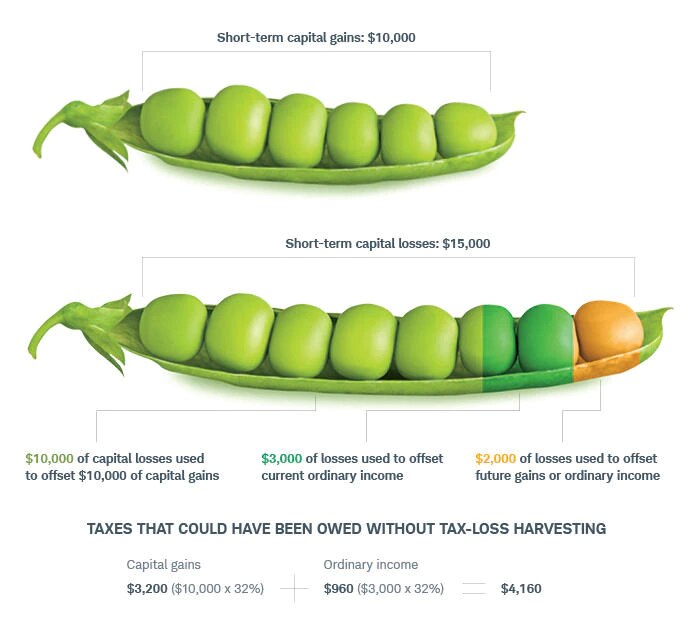

Using a tax loss to get a tax break

A hypothetical investor who realized $10,000 in short-term capital gains and $15,000 in capital losses could use tax-loss harvesting to reduce their tax bill—this year and in future years.

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Assumes a 32% combined federal/state marginal income tax bracket, with short-term capital gains taxed at ordinary income tax rates. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent a specific investment product and the example does not reflect the effects of fees.

2. You want to reduce your taxable income

If you don't have investment gains to offset, or if you realize more losses than gains, you can use up to $3,000 in losses to reduce your ordinary income this year—and every year thereafter—until the entire loss is accounted for.

3. You need the cash

There's an adage among traders: Let your winners run. If you don't want to sell your winners prematurely, it might make more sense to generate the necessary income by selling your losers—which may allow you to offset up to $3,000 a year in ordinary income in the process.

4. The investment no longer fits your strategy

Regardless of whether an investment has lost or gained value, you should never keep it if it no longer fits your strategy. That said, it can be hard to let go of an investment that's lost value, thanks to the break-even fallacy, or our instinct to wait to sell an investment until it rebounds to our purchase price.

But holding on to the investment in hopes of a turnaround could erode your returns further. Taking the loss could allow you to get your portfolio back on track more quickly—and potentially offset capital gains and/or ordinary income.

Other considerations

If you've decided to sell some losers, it's important to understand a few of the applicable tax rules before you act:

Short- vs. long-term capital gains

- Short-term capital gains are taxed at ordinary federal income tax rates, which, for many taxpayers, are higher than the long-term capital gains rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your income level.

- Any losses first must be applied to gains of the same type before they can be applied to gains of a different type. For example, if you have short- and long-term gains, first you must use any long-term losses to offset your long-term gains; then you can use any remaining long-term losses to offset your short-term gains.

Wash-sale rule

- If you plan to take a loss and reinvest the proceeds, be mindful of the wash-sale rule: You can't use the losses to offset gains if you purchase the same, or a "substantially identical" investment, within 30 days before or after the sale.

- Unfortunately, there's no clear guidance on what constitutes a substantially identical investment. Stocks are fairly straightforward, but for exchange-traded funds and mutual funds, it's best to err on the side of caution by selecting a fund that tracks a different benchmark or has a markedly different investment mix.

A financial planner or qualified tax advisor can help you make the most of any investment losses—without running afoul of the IRS.