Guide on Taking Social Security: 62 vs. 67 vs. 70

Deciding when to take Social Security depends heavily on your circumstances. You can start collecting benefits—based on your work history—as early as age 62 (or sooner if you're disabled), wait until your full retirement age, or hold off until age 70. (If you're a survivor of another Social Security claimant, you can start receiving benefits—based on their earnings—as early as age 60). While there's no "correct" claiming age for everybody, the rule of thumb is that if you can afford it, delaying Social Security can pay off over a long retirement.

Ahead, we'll look at important topics including:

- The full retirement age

- Taking Social Security at ages 62 to 67

- Taking Social Security at age 70

- Taxes on Social Security

- The future of Social Security

- And more

What's full retirement age?

You become eligible to receive full Social Security benefits at full retirement age (also known as "normal retirement age"), which depends on your birthday.1 If you were born in 1957 or earlier, you've already reached full retirement age. Under current law, if you were born in 1958 or later, your full retirement age can be anywhere between 66 and 8 months and 67 for those born in 1960 and after.

- If you were born in...

- Your full retirement age is...

-

If you were born in...1957 or earlierYour full retirement age is...You've already hit full retirement age

-

If you were born in...1958Your full retirement age is...66 and 8 months

-

If you were born in...1959Your full retirement age is...66 and 10 months

-

If you were born in...1960 or laterYour full retirement age is...67

How much will my Social Security benefits be?

Your annual Social Security statement lists your projected monthly benefits between age 62 to 70, assuming you continue to work and earn about the same amount through those ages. You can request a copy of your annual statement or view it online on the Social Security Administration (SSA) portal.

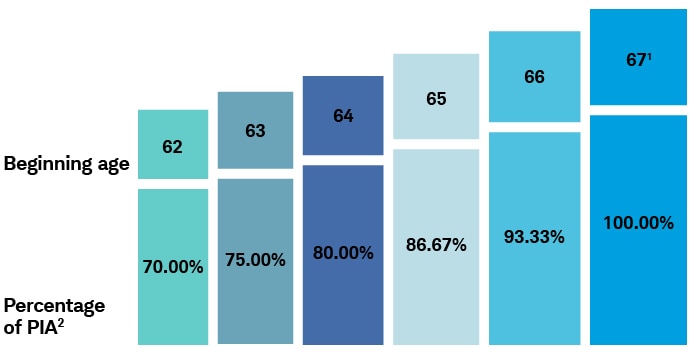

What if I take Social Security benefits early? Age 62 through 67

If you choose to take your own (not your spouse's) Social Security benefit early, be aware that the payments will be permanently reduced by five-ninths of 1% for each month before your full retirement age. If you start more than 36 months before your full retirement age, the worker benefit decreases further by five-twelfths of 1% per month for the rest of retirement.

For example, if your full retirement age is 67 and you elect to start benefits at age 62, the SSA will calculate your payments based on the fact that you are taking the benefit 60 months before full retirement age—a 20% reduction for the first 36 months (five-ninths of 1% times 36) and another 10% (five-twelfths of 1% times 24) for the remaining 24 months, cutting your monthly Social Security benefits by a total of 30%.

Effect of taking retirement benefits early (DOB: January 2, 1960)

Source: SSA.gov

For illustrative purposes only.

1Represents full retirement age based on DOB January 2, 1960

2PIA = The primary insurance amount is the basis for benefits that are paid to an individual.

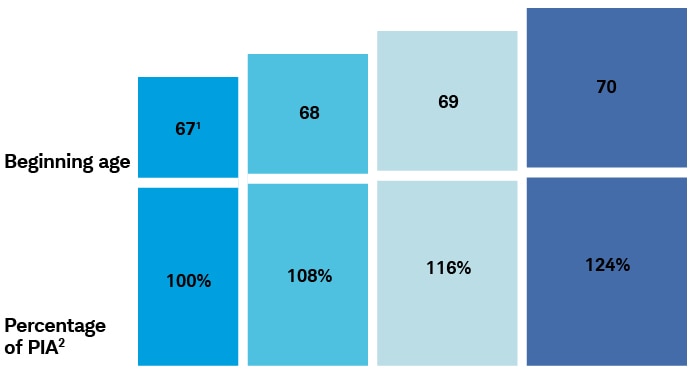

What if I delay taking my Social Security benefits to age 70?

If you retire sometime between your full retirement age and age 70, you typically earn a "delayed retirement" credit (DRC) for your own benefits (but not spousal benefits). The higher baseline would last for the rest of your retirement and serve as the basis for future increases linked to inflation. In no situation should you postpone benefits past age 70.

For example, say you were born in 1960, and your full retirement age is 67. If you start your benefits at age 69, you would receive a credit of 8% per year multiplied by two (the number of years you waited). This means your benefit amount would be 16% higher than the amount you would have received at age 67. (This doesn't include any potential additional cost of living adjustments for inflation from age 67 to 69.)

Effect of delaying retirement benefits (DOB: January 2, 1960)

Source: SSA.gov

For illustrative purposes only.

1Represents full retirement age based on DOB January 2, 1960

2PIA = The primary insurance amount is the basis for benefits that are paid to an individual.

How should I decide when to take Social Security benefits?

Consider the following factors as you decide the best age for you to begin taking Social Security.

Your cash needs

If you're contemplating early retirement and you have sufficient resources (for example, an investment portfolio, a traditional pension, and other sources of income), you can be flexible about when to take Social Security benefits.

If you'll need your Social Security benefits to make ends meet, you may have fewer options. You may want to consider postponing retirement or working part-time until you reach your full retirement age—or even longer—so that you can maximize your benefits.

Your life expectancy

Taking Social Security early reduces your benefits, but you'll also receive monthly payments for a longer period of time. On the other hand, taking it later results in fewer Social Security checks during your lifetime, but delaying also means each check will be larger.

If you think you'll beat the average life expectancy, the higher payout for waiting to collect Social Security can be particularly beneficial. Remember, though, that the average is just that—an average. If you expect to have a shorter life expectancy or are in poor health, then early withdrawals might make sense.

A quick note about life expectancy

According to the SSA, the average life expectancy for a 65-year-old is around 84 years for males and 87 for females. Married individuals tend to live even longer, with an average probability of at least one spouse living to age 90. To compute your own life expectancy, use the SSA's life expectancy calculator.

Your marital status

If you're married, start by taking your spouse's age, health, and benefits into account, particularly if they are the higher earner. For example, at full retirement age, you can take either 100% of your own retirement benefits or 50% of your spouse's, whichever is higher.

If you're divorced and you were married for 10 years or more, you can receive benefits based on your ex-spouse's Social Security record (up to 50% of their full retirement benefits). Take note that if your ex-spouse uses your record, this won't impact your or your current spouse's benefits.

It's important to make the most effective use of the combination of your own, spousal, and survivor benefits, working with a financial planner if possible.

Your employment status

Earning a wage (or even self-employment income) can reduce your benefit temporarily if you collect Social Security. If you haven't reached your full retirement age, $1 in benefits will be deducted for every $2 you earn above the annual earnings limit ($23,400 in 2025). In the year you reach your full retirement age, the reduction falls to $1 in benefits for every $3 you earn above a higher limit ($62,160 in 2025).

However, the month you hit your full retirement age, your benefits are no longer reduced, no matter how much you earn. In fact, the SSA will recalculate your Social Security payments to include the deducted amounts, resulting in higher benefits.

Don't use the reduction as the sole reason to cut back on working or worry about earning too much. That said, if you're still working, you may want to postpone Social Security either until you reach your full retirement age or until your earned income is less than the annual limit.

Consider taking Social Security benefits earlier if...

- You're no longer working and can't make ends meet without your benefits.

- You're in poor health and don't expect the surviving member of the household to make it to average life expectancy.

- You're the lower-earning spouse, and your higher-earning spouse can wait to file for a higher benefit.

Consider waiting to take Social Security benefits if...

- You're still working and make enough to impact the taxability of your benefits. (At least wait until your normal retirement age so benefits aren't further reduced due to earnings.)

- Either you or your spouse are in good health and expect to exceed average life expectancy.

- You're the higher-earning spouse and want to be sure your surviving spouse receives the highest possible benefit.

Social Security and Medicare

If you start Social Security benefits early, you'll automatically be enrolled into Medicare Parts A and B when you turn age 65. Be aware that if you decide to wait to collect Social Security past age 65, you may still need to sign up for Medicare. In some circumstances your Medicare coverage may be delayed and cost more if you don't sign up at age 65.

What about taxes on Social Security?

Social Security benefits may be taxable, depending on your "combined income." Your combined income is equal to your adjusted gross income (AGI), plus nontaxable interest payments (e.g., interest payments on tax-exempt municipal bonds) and half of your Social Security benefit.

As your combined income increases above a certain threshold (from earning a paycheck, for instance), more of your benefit is subject to income tax—up to a maximum of 85%. For help, talk with a CPA or tax professional.

What if I change my mind?

You may withdraw your Social Security application within the first 12 months and pay back to the government any benefits you received (including Medicare payments, if applicable, and taxes deducted). You'll have to reapply later when you want to restart your benefits, but be aware that you may cancel your application only once.

For example, let's say you elect to receive early benefits at a reduced rate at age 62, but then after a few months, you decide to go back to work. You could withdraw your Social Security application, return the months' worth of benefits, and then wait until you quit your job or need the income to restart your monthly checks at a higher payout.

Once you reach full retirement age, you also have the option to voluntarily stop benefits at any point before age 70 to receive delayed retirement credits (spousal benefits will be stopped as well). Benefits will automatically restart at age 70 at a higher amount—unless you choose to collect benefits before then.

Note that when you withdraw your application or stop your benefits after full retirement age, you must specify if your Medicare coverage—if you have it—should also be discontinued.

Can my kids inherit my Social Security benefit?

In addition to your spouse, dependent children and even grandchildren may be eligible to receive benefits when you die, become disabled, or retire. To qualify, your dependent must be unmarried and meet certain age requirements:

- Be under the age 18

- Or under age 19 and attending a primary or secondary school full time

- Or any age if they are disabled before the age of 22

For minors, payments stop when they turn 18. Benefits end for students when they graduate or two months after their 19th birthday, whichever comes first. Disabled family members can continue collecting your Social Security until they marry.

The rules are complex, especially around disability. Make sure to consult the appropriate benefit specialists at the Social Security Administration (SSA).

What is the future of Social Security?

For years, the Social Security Board of Trustees has warned against a projected shortfall that would require the program to reduce benefits to recipients. In 2014, the board estimated a 23% cut in benefits after 2033; today, it predicts about a 17% reduction after 2035. That, of course, is only if Congress fails to act, which seems unlikely, and it's doubtful that Social Security retirement benefits would go away entirely.

The most obvious solutions include raising the retirement age or increasing the payroll tax rate, both which Congress has implemented in the past to address similar insolvency concerns. By some estimates, raising the payroll tax just 3.33 percentage points to 15.73%—the cost of which is split evenly between employer and employee—would allow the program to remain fully solvent for another 75 years.2

Some solutions, however, are likely to be unpopular with Congress and voters alike, and we may not see any changes from Congress until the eleventh hour. If you're skeptical about the future of Social Security or wary of potential changes, you may be tempted to start benefits early, assuming that it's better to have something than nothing. Instead, use your concern as a good reason to save more—and earlier—for your retirement.

The bottom line on Social Security

If you have a choice and are in good health, think seriously about waiting as long as you can to claim Social Security benefits (but no later than age 70). A long retirement coupled with uncertainty about markets and inflation are the biggest risks. Delaying Social Security, if you can, is effectively an insurance policy against those challenges.

Your situation may differ, however, and you'll want to consider several factors. A financial planner and tax professional can help you determine the role Social Security will play in your retirement planning.

1If your birthday is on the 1st of the month, the SSA determines your full retirement age and benefit as if your birthday were in the previous month (December of the year before if your birthday is on January 1).

2The 2024 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds, ssa.gov, 05/07/2024, https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2024/tr2024.pdf.