Getting a Slice: How IPO Shares Are Priced and Allotted

Initial public offerings, or IPOs, often get a lot of press. How well a big-name company does in its market debut can set the tone for trading in similar companies and even in the wider market. Companies often go public in order to tap into capital markets to leverage market growth to further expand their business.

Also, those who are able to buy shares at a company's initial price may have a chance of making a good bit of money. But as with anything stock related, the higher the reward, the higher the risk.

For retail investors who want to try their hand at IPO investing, the truth is that it can be pretty hard to get shares because most of them end up going to institutional investors. Like much else in the economy and stock market, IPO shares allotment boils down to supply and demand Before taking the plunge, here are some things you may want to consider about how an IPO works, how IPO shares are allotted, and how to participate in an IPO.

In the IPO process, companies going public want to sell as many of their shares as they can at the highest price they can get. So, they hire investment bankers at places like Goldman Sachs (GS), Credit Suisse (CS), or Morgan Stanley (MS) to underwrite the offering and allocate shares to the highest bidders.

There are often multiple underwriters on the same IPO, and this group of investment bankers is called a syndicate. They market IPO shares primarily to institutional investors such as pension funds, hedge funds, or banks.

The part of the process where investment bankers try to sell shares is called a road show. During the road show, bankers can gauge demand for the offering and zero in on how much money they can get for shares based on the demand for a finite supply. Before the road show, bankers have only an estimated range for an IPO stock price.

Slices of pie

In typical IPOs, most of the shares will go to institutional investors. It's not that investment banks want to cut out individual investors—it's just that they're trying to sell as many shares as possible, and big players have the financial firepower to buy big blocks of shares.

If a well-known company that investors are keen to buy shares from is going public, it can be difficult for retail investors to get an allocation from their broker's pile of shares. When there's more demand for shares than there is supply, an IPO is called oversubscribed. Individual investors have a better chance of getting in on an undersubscribed offering, but the risk is that demand is low for a reason, such as a company not having strong fundamentals.

Trickling down

Not all brokerages use the same allocation formula. Some use a lottery system, while others base the decision on how valuable a client you are.

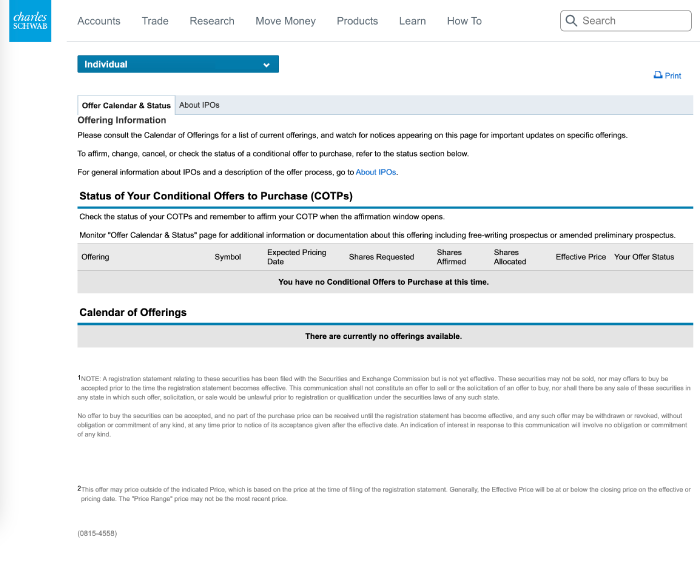

Schwab clients can find new IPOs on thinkorswim® or the IPO Offer Calendar & Status page on schwab.com.

Pros and cons of investing in an IPO

One potential advantage of investing in an IPO can be that you get in at a price that ends up being below the price at which shares begin trading in the secondary market (meaning on stock exchanges). That can happen when there's lots of demand from investors in the secondary market even if shares are expensive. It can also be the case that the investment bankers and the road show end up underpricing an IPO, offering what many may perceive as a bargain.

In 2020's busy IPO market, newly listed companies saw an average first day return of 38%, according to Nasdaq Economic Research. From 1980 through 2023, the average "IPO pop" was 18.9%, according to research from NASDAQ. If you bought in to one of those at the IPO price and simply sold it at its closing price, you could pocket a tidy sum—assuming you weren't subject to a holding period. Many companies enter a lock-up period following the launch of an IPO, typically from 90 to 180 days. During that time, company insiders aren't allowed to sell their company shares. This period is designed to stabilize the price of shares after an IPO is launched; it prevents insiders of the company from depressing the value of the stock by flooding the market with their shares. They might also be prevented from selling company stock during post-IPO blackout periods, which often occur before quarterly or annual earnings releases.

But there's also the risk that IPOs flop on their first day. Take Uber Technologies (UBER), for example. It was one of the most anticipated IPOs of 2019, but its shares lost more than 7.6% on its first day. Home security company ADT (ADT) lost 11.5% in its 2018 debut, and China Petroleum & Chemical (SNP) lost 4.4% on its first day of trading in 2000.

Sometimes stocks can pop on their first day only to subsequently sag. Take Lyft (LYFT). Its March 2019 IPO price was $72 per share. It closed at $78.29 on its first trading day but fell about 20% during the week of April 8, 2019.

Sometimes it can be better wait to see how market conditions and demand for a newly public company's shares shake out. This is particularly true if, as an investor, your objectives tend to keep your focus on fundamentals rather than narrative, potential, or hype.

Don't succumb to FOMO (fear of missing out)

Perhaps the IPO page on the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) website put it best: "An IPO gives the investing public an opportunity to own and participate in the growth of a formerly private company. By their nature, however, IPOs can be risky and speculative investments."

Like any investment, it's a good idea to research any company that is planning to IPO to determine if the stock is a fit within your portfolio to help you reach your financial goals. This isn't always the case, and newer companies in unproven industries can require more research to fully understand their businesses and risks.

Some ways to do this before investing in an IPO include reading the SEC Form S-1 before shares are listed, finding out the length of the lock-up period—that is, how long insiders are prohibited from selling shares after the IPO—and checking whether there's a holding period that keeps IPO investors from selling shares soon after a debut (a practice called "flipping").

Also, as with other types of investing, consider doing a gut check to make sure you're not getting so caught up in IPO hype that you lose sight of the prudent investing strategies you may have adopted and found to work for you in the past.

Keep in mind, IPOs are generally regarded as high-risk investments. Schwab is not recommending the purchase of any particular IPO, and it's up to you to decide whether an a particular IPO is suitable for you. Schwab clients wishing to participate in an IPO offering should become familiar with the "Steps to Participate in an Offering" and closely monitor the Offer Calendar & Status page available by logging into their account on Schwab.com.