Inflation, Deflation, and Stagflation Explained

When people think of inflation, they often view it through the lens of everyday items like a dozen eggs, a loaf of bread, or the price of gas at the pump.

Economists generally define inflation as the increase in prices for goods and services over a given time frame, like monthly or annually. While the average person most often just notices that increase in prices, the change in the cost of goods can take many forms, such as inflation, deflation, and disinflation. You may have even heard of "stagflation." So, what do these different terms mean and how can changes in inflation impact financial markets and investment portfolios?

Inflation lingo

A few different terms are used to describe potential trends in prices. It's important to know them all:

- Inflation: The increase in the price of goods and services in a country over a time frame, such as one year.

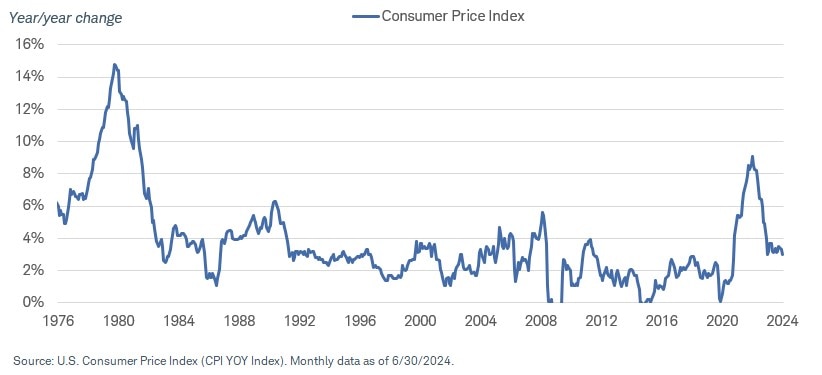

- Disinflation: When the inflation rate declines but stays positive. For example, in the U.S. annual inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), fell to 3% in June 2024 from the 9.1% high reached in June 2022. With disinflation, inflation goes down, but prices do not. They might even continue to go up, although at a much slower rate.

- Deflation: A period of falling prices. In late 2020 and early 2021, Japan saw consumer prices fall, resulting in periods where inflation dipped below 0%.

- Stagflation: A period of high inflation accompanied by weak economic growth. During the 1970's oil crisis in the United States, for example, inflation was rising and hit double digits in 1974. At the same time, the economy contracted for several consecutive quarters and gross domestic product (GDP) turned negative, amid higher employment.

- Hyperinflation: A very high and accelerating rate of inflation. Some lesser developed countries have fallen victim to hyperinflation, such as Zimbabwe from March 2007 to mid-2008 when prices doubled nearly every day.

Ways to measure inflation

- Headline inflation is a measure of price changes that looks at a broad array of goods and services in the economy.

- Core inflation is a measure of underlying inflation. It removes food and energy prices, which tend to be volatile, from the headline number.

- CPI is arguably the most widely watched measure of inflation; it tracks the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services, which represent the average household's purchases.

- The Producer Price Index (PPI) measures the price change over time in what's paid to U.S. companies that produce and manufacture all the goods people buy. It's a useful comparison because it gauges the prices that manufacturers and producers pay rather than what consumers are paying.

For consumers, the rate of inflation is important because it impacts purchasing power. The more prices increase beyond incomes, the more budgets get squeezed, especially for those living on a fixed income like many retirees. Periods of disinflation are welcome news because consumers' purchasing power isn't eroding as quickly, as long as incomes are steady or rising.

Periods of deflation are typically viewed as a bad omen because falling prices for goods and services indicate a weak economy, sluggish demand, and falling asset prices. Also, when people believe prices are heading down, they might delay purchases. Less spending typically translates into less profitability for retailers and producers, which can result in higher unemployment.

Except for modest decline in prices in 2009, the United States hasn't experienced any meaningful bouts of deflation in more than 60 years. And, while there were some fears that the United States might see a period of stagflation after the pandemic, the economy never entered a protracted recession; instead, the economy experienced some "rolling" recessions, where certain industries like housing suffered, but other parts of the economy remained resilient. Periods of stagflation have been relatively uncommon as well.

What causes inflation?

While inflation has many influences, the primary cause is an imbalance between supply and demand in the economy. If demand for goods, services, or labor exceeds the economy's capacity, then prices rise.

It's generally accepted that a country's monetary and fiscal policies can influence inflation because it can discourage or encourage spending or boost the production of goods and services. Consequently, it can have a big impact on inflation; if there's extra money, the country's currency becomes less valuable, making things more expensive.

When there's a significant change in the production of goods, it typically impacts prices too. If there's a breakdown in a supply chain or some other unexpected event, for example, it can affect entire industries and the products they sell. During the pandemic, people stuck at home spent money shopping online for on goods because they couldn't spend money on services. At the same time, they couldn't get goods easily because of supply-chain bottlenecks. As the economy opened up, people were less interested in buying many of those stay-at-home goods. Instead, they wanted the haircuts, dinners out, and vacations that they had put off. This sent services inflation soaring.

Similarly, rising oil and gasoline prices (or other raw materials commonly used in production) can lead companies to charge higher prices to offset their increased costs from transporting or producing goods, which can lead to higher inflation. Tariffs, which increase the cost of imported goods, can also have an impact on a country's inflation rate. Natural disasters, changes in regulation, labor costs, and fluctuations in a country's currency are a few other factors.

Lastly, the mere expectations of inflation can have a self-feeding effect. When individuals or companies anticipate higher prices, they begin to price in those expectations into products, contracts, and wage negotiations. If those expectations are based on what has happened in the recent past, they might ask for higher wages or better pricing for their products or contracts in the future—a phenomenon known as inflation "inertia."

Inflation and interest rates

For investors, inflation can be viewed as a positive and a potential negative. For example, stocks, real estate, and some commodities have historically increased in value over the long term along with inflation. Some investments, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), are directly linked to the pace of inflation and offer better returns when inflation increases.

Investors are concerned about not only declining purchasing power but also the potential impact of inflation on interest rates. The Federal Reserve has a mandate to keep a lid on inflation and its primary tool for combatting rising prices is to raise interest rates, which it did multiple times from March 2022 to July 2023.

Higher interest rates are nice for income-oriented investors because they can potentially earn more income on the higher yields. At the same time, higher rates can make it more difficult for individuals and businesses to borrow money and spend, which can be a headwind for business activity and economic growth. On the other hand, when the Federal Reserve lowers rates, the intention is typically to stimulate economic growth without igniting the forces of inflation.

This time around, the Fed is likely to cut rates to hopefully maintain a restrictive policy rather than as a means to stimulate the economy. The Fed focuses on the "real" interest rate, or the inflation-adjusted rate. The "real" federal funds rate can be calculated by subtracting the inflation rate from the federal funds rate. Cutting the interest rate allows the real rate of interest to stay steady while the inflation rate falls.

Economically sensitive sectors of the stock market and other assets that tend to benefit from robust economic growth, like energy or basic materials, can sometimes see an increase in volatility if there's a growing perception that a central bank will begin aggressively tightening monetary policy to fight inflation. That volatility can mean sudden market downturns or corrections. The opposite is true if markets begin pricing in rate cuts. Of course, there are many variables that affect asset prices and interest rates aren't the only drivers of long-term returns. Nevertheless, tuning in to inflation data can sometimes help investors get a sense of the next direction of a central bank's monetary policy and future interest rates.

Bottom line

Periods of deflation and stagflation are relatively rare in modern history. Inflation is more common and can be a problem when prices rise too rapidly relative to incomes because household budgets can get squeezed. At the same time, higher inflation can lead to higher interest rates and opportunities to earn more on savings vehicles like money market funds, certificates of deposit (CDs), or other higher-quality investments like U.S. Treasuries, investment-grade corporate bonds, and municipal bonds.

Investing in assets like real estate, gold, and equities has historically been effective in keeping pace with inflation over the long term. However, those same assets can experience increased volatility if high inflation triggers aggressive rate hikes from the Federal Reserve. It's part of the reason investors pay such close attention to asset allocation and whether they're in growth-oriented investments or interest-bearing ones. It usually depends on the investor's time horizon, financial goals, and tolerance for risk.