Options Strategy: Selling Put Spreads to Buy Stock

Stock traders and investors often enter orders to buy shares at a price that's lower than the prevailing market price. But did you know certain options strategies can sometimes be used to pursue a similar objective?

By selling put options, some option traders use strike prices as potential stock entry points. Remember, if you sell a put and the stock falls below the strike price on or before expiration, you'll likely be assigned, meaning you'll be buying 100 shares of the stock at the strike price for every standard put option contract. And, really, early assignment is possible at any time during the duration of the option contract, but it is especially likely if the stock drops below the strike price.

One main risk of selling put options is that you're obligated to buy the stock at the strike price no matter what happens, even if the stock falls all the way to zero. So, if you're interested in putting a limit on your risk, you can choose a defined-risk strategy, such as selling a put spread. But before you consider this strategy, it's important to understand the mechanics, as well as the risks, of selling put spreads to potentially buy stock.

Here's an example

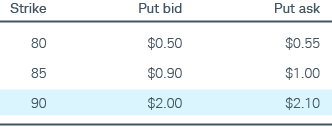

Let's say a stock recently rallied above a technical resistance level at $90 and is currently trading at $100. Some traders might now see that $90 level as an area of possible support and thus a possible entry level. If you're an option trader who's interested in buying the stock at $90, you might decide to sell a put spread where the short put has a strike price of $90. Consider the example option chain below.

For illustrative purposes only.

Defining the risk with a put spread

Being short the 90-strike put means you're taking on the obligation to buy the stock at $90, which is, initially anyway, your objective behind this trade idea. However, your opinion of the stock might change if you wake up to find the stock trading at $70 or lower. The possibility of a large drop in the stock price is why you might consider selling a put spread rather than an uncovered short put.

Using the theoretical prices from the table above, you could, for example, sell the 85-90 put spread by selling the 90-strike put for $2 and buying the 85-strike put for $1 ($2 – $1 = $1). Both puts are on the same underlying stock and have the same expiration. Because the options multiplier is 100, for each spread you sell, you'd collect $100 minus transaction costs. Your potential loss on the trade is then limited to $400, which is the difference between the two strikes (x 100) minus the $100 credit from selling the spread. And again, remember to include transaction costs.

Explaining the math

Stock falls below $90 but not below $85

If the stock drops below $90 before expiration (but not below $85), you'll likely be assigned on your put and buy the stock at $90 per share, just like you planned. At that point, you'd have a hedged "protective put" position consisting of stock at $89 per share (the $90 per share paid for the stock minus the $1 for selling the spread) and an 85-strike put. You'd still participate if your forecast is correct: The stock finds support around $90 and moves higher. At the same time, holding the lower strike put gives you the right to sell the stock for $85 if things go south before expiration.

Depending on market conditions and time left to expiration, holding the stock after the 90-strike put is assigned and closing the 85-strike put might be another possibility, leaving you with shares at a cost of $90 minus the credit for selling the spread and minus any credit for selling the 85-strike put. Once the 85-strike put is closed (or expires), the trade risk is similar to holding a stock bought for $90 per share minus any credits.

Stock falls below $85

But if the underlying stock falls below $85, the 90-strike put will likely be assigned, and you could potentially exercise the 85-strike put to cover assignment, meaning you'd buy the stock for $90 and immediately sell it for $85. Alternatively, you could exercise the put and sell the stock short at $85, then cover the short position once the 90-strike put is assigned. Either way, if the position is exited through exercise and assignment, there is no remaining position in the underlying stock, but you'd book a $400 loss (or $500 on the stock position minus the $100 received) per spread. At that point, you can decide if you want to buy the stock at its new (lower) prevailing price or perhaps sell another put spread with lower strikes. Note that if the long put is exercised, any remaining time value is lost. Therefore, in some instances, the optimal exit strategy after a big drop in shares and assignment on the higher strike put might be to sell the shares and sell (rather than exercise) the put with the lower strike.

Stock stays above $90

And if the stock stays above $90 through expiration? The put spread will likely expire worthless, and you'll keep the $100 credit minus transaction costs. At that point, you can move on to something else, or if your forecast hasn't changed, you can potentially open a similar put spread in a further expiration.

A word on strike selection

You can also tailor the options spread to meet your own personal risk guidelines. By widening the spread, say to an 80-90 put spread, you can collect a larger credit in exchange for more risk. By selling the 90-strike put and buying the 80-strike put, for example, your credit would be $1.45 ($2 – $0.55 = $1.45), which is $145 per spread, in exchange for a maximum risk of $8.55, or $855 per spread (the difference between the strikes, $10, minus the credit you received, $1.45, times the multiplier). Again, don't forget those transactions costs.

How does the put spread differ from using a limit order?

One difference between placing a limit order to buy shares at $90 versus selling the put spread is, with the put spread, the stock might trade below the strike price before expiration, but then rally above it. In that case, assuming you weren't assigned early while the stock was trading below the strike price, your spread will finish out of the money, you will not be assigned on the 90-strike put, and thus you will not be long the stock at $90. For example, if the stock price falls to $89, and then recovers and rises to $100 before expiration, you'd have missed out on that opportunity. The flip side, however, is that if the stock never drops below $90, you'll still keep the credit from selling the put spread.

Bear in mind that the long option holder can choose to exercise their option at any time prior to expiration, so it is possible to be assigned even if the stock is below the strike for only a short time prior to the expiration date.

Such is the nature of options trading—there's always a risk and reward trade-off.