Passing Financial Values to the Next Generation

Silicon Valley is teeming with garages famous for giving birth to much of the modern technology industry. One of them belonged to Derek and Susan Hine. That's where Derek, an English-born aeronautical engineer who previously served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, worked on the inventions that helped jump-start his financial success. One such venture was Hine Design, a robotics company he created with his brothers and sold in 1998 to Asyst Technologies for $24 million.

But for the Hine family, success has always been about more than money; it's been about creating shared family values and a clear sense of purpose. "My parents taught us there are lots of ways to manage money, but that there's nothing like creating value based on your beliefs," says Graham, the older of Derek and Susan's two sons.

Graham and his brother, Roger, had front-row seats to their father's businesses as kids—eventually becoming close collaborators. Together the three men helped create Wave Glider, an unmanned wave- and solar-powered robot that collects marine data. Originally developed for humpback whale research, Wave Glider has multiple applications for maritime security—which is one reason Boeing acquired its parent company, Liquid Robotics, in 2016.

Today, Graham is co-founder and director and Roger is chief technology officer and director of ePlant, a company that uses artificial intelligence to remotely monitor the health of trees and other plant life—a venture inspired in part by a love of the outdoors inherited from their parents.

Of course, subsequent generations don't always carry forward the same kind of principled work ethic and wealth management savvy as their parents and grandparents—hence the adage "shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations." So, with an estimated $85 trillion expected to pass from older Americans to Gen X and millennials over the next two decades,1 how can families prepare younger generations for the responsibility that comes with wealth?

Here are some dos and don'ts for those looking to instill their core values and maintain their legacy years into the future.

DO: Talk about money—early and often

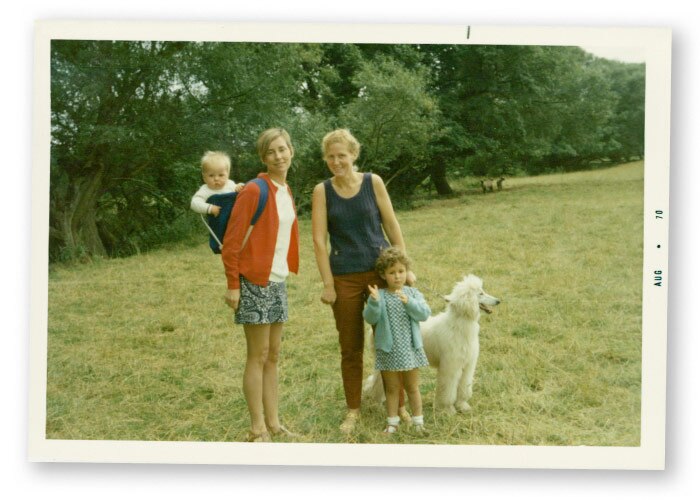

Susan and Graham (left) explore Golden Gate Park in San Francisco with family. "Somehow or other, we always ended up outside," Susan says.

Communication is key to introducing financial education and your core beliefs to your children. For example, when shopping with toddlers, you can teach them how to make sound financial decisions by explaining that they can't get everything they want because the money is needed for something else.

With school-age children, you can use their allowance as a learning experience by allocating a certain percentage to spending, saving, and giving. You can even pay them interest on their savings to teach them the benefits of delayed gratification and compound growth. Graham recalls his father carefully tracking investments in a notebook and discussing his approach with both boys.

If you expect your kids to work for their own money as teens and young adults, they need to understand that from an early age. "Derek and I were wartime Brits," Susan says. "For us, you had to not only earn money but also save money—always." It's an approach the couple instilled in their sons. "We had Graham get a paper route as a young boy to earn money for the things he was passionate about. If you're given that money on a silver platter, your level of commitment will never be the same," she says.

Self-conscious parents may hope older kids won't notice their family's wealth, and how much of your financial life you decide to share with them depends on the child and the situation. But in the age of social media, affluence can be difficult to disguise. If your child questions you about your wealth, you might start the conversation with questions like, "Where do you think our money comes from?" or "How can we use our resources for the wellbeing of others?"

Likewise, there are no hard-and-fast rules for when to start sharing your long-term goals as well as your estate and family legacy plans with your children—except you should do so while you're still alive. (See "Don't: Assume your estate plan is sufficient.") Discussing your wishes with loved ones—particularly around the distribution of assets—can not only help ensure a smooth transition of your wealth but may also minimize conflict and maybe even prevent potential lawsuits.

Derek and Susan invited both sons into their estate-planning conversations early on. "Roger and I have met with our parents' lawyer and know exactly what's in their wills," Graham says. "We also regularly sit in on meetings with their Schwab advisors so we're all on the same page."

If you intend to leave a tangible legacy—be it a business, a charitable trust, or even a foundation—you should similarly invite your heirs into the planning process by discussing, for example:

- What do we want to accomplish together?

- How can we serve future generations?

- What's your vision for the family business or for philanthropic giving?

For the Hines, ePlant's ongoing success is a priority, as is bequeathing additional resources to local land preservation efforts and other charities they support.

A collective family wealth mission statement can help, especially for those hoping to beat the odds and preserve their family's wealth for generations.

Creating a shared vision

A family wealth mission statement is key to a lasting legacy.

One of the biggest risks to any family legacy is not mismanagement but misalignment. That's where a family wealth mission statement comes in. In essence, it's a document that outlines a family's financial goals, intentions, and personal values regarding their wealth to help guide current and future decision-making about your shared legacy. It's not legally binding, but a family wealth statement can reduce conflicts and help give you peace of mind the collective wealth is deployed in ways that honor your own values as well as your financial strategy.

DO: Live your values

Derek (left) and Roger test an early Wave Glider prototype in Monterey Bay, California.

One way to pass along your personal values on money management is by talking with your family about the purpose of excess wealth—and then setting an example with your own financial habits.

The Hines focused less on possessions than on experiences, many of them involving activities like camping, hiking, and skiing. "Somehow or other, we always ended up outside," Susan says, which was consistent with her own upbringing in England. "When I was growing up, we didn't have the money to spend on going out, so we'd pack up the car and head to the woods or a lake." If fancy hotels and first-class airline tickets are your thing, that's perfectly fine—just be aware that if that's all your kids know, that's the lifestyle they are going to expect to maintain, no matter what you tell them.

"Leaving the bubble of wealth is essential," she advises. "Take them to places where they can be of help."

Susan volunteered extensively at Filoli Historic House & Garden in Woodside, California, particularly in the nature education program for kids, leading guided hikes and workshops. She recently dedicated time to help maintain the landscape and mitigate fire risk in her California community. She never pressured her sons to participate in her volunteer activities, but the example she set—and her and Derek's passion for the great outdoors—made an impression.

"We inherited our love of the land from them," Graham says.

DO: Be clear about what you will and won't pay for

If you set rules for making your kids self-sufficient, tell them early—and stick to them. The Hines, for example, told their sons they would pay for tuition, room and board, and other basics, no matter what college they got into. "But we had to work for our own spending money," Graham says. "If I wanted to go on a date or take a trip to the beach, it was on me. As it happens, the summer jobs I took to fund my nonessentials actually set me up for success on my current career path."

The same holds true if you intend to ease their journey from college student to fully independent adult by gradually pulling back financial support. Just make sure to discuss your timeline ahead of time so they aren't caught off guard and can prepare to embark on their own financial journey.

DON'T: Assume your estate plan is sufficient

Although estate planning is critically important, no collection of legal documents can take the place of values learned firsthand. "The most successful legacies are those built by families whose members are truly in sync with one another," says Alex Rich, a senior financial consultant at Schwab who has worked with the Hines for nearly five years.

And while some parents use estate planning to try to nudge individual heirs toward a desired path—such as by incentivizing college graduation or rewarding the birth of a grandchild—even the best-laid plans won't ensure success. Expectations that may seem suitable today may not be appropriate in the future and could potentially have negative consequences if your kids view such agreements as being manipulative.

As for Susan and Derek, they never tried to control the direction of their sons' lives—and they aren't dictating the terms of their inheritance, either. "We trust them implicitly," Susan says.

"I feel really fortunate we got that drive to create from our parents," Graham adds. "If you have that, you'll maintain what your family has and add to it. If you don't and you're comfortable living off privilege, it's a path to the exhaustion of wealth, no matter how much your family may have accumulated."

DON'T: Wait too long

Roger (left) and Graham calibrate the sensors on one of ePlant's AI-powered tree-monitoring devices.

Without prioritizing time together, it's hard to pass on your values to your kids. While Derek worked hard, he made sure to step away from work on weekends and vacations. "Despite the extreme demands early in his career, he always found time for the family," Graham says.

Several years ago, Derek began showing signs of dementia and voluntarily gave up flying his beloved experimental aircraft, but his influence endures. "I often see brilliant people who have gotten to where they are by working 60 or 70 hours a week," Alex says. "As financial planners, we can help reinforce the notion it's OK to step off the treadmill in favor of spending more time with family. There's a time to sow and a time to reap the rewards, and there's no greater reward than quality time with your kids and the impact that comes with it."

1Cerulli Associates. "Cerulli Anticipates $124 Trillion in Wealth Transfers Through 2048," cerulli.com, 12/05/2024.