RMD Strategies to Help Ease Your Tax Burden

Many of us save money in traditional 401(k)s, individual retirement accounts (IRAs), or other tax-deferred investment vehicles assuming that when we start withdrawing money in retirement, our income tax rate will be lower. However, it's not unusual for retirees to find themselves in the same or even a higher tax bracket when required minimum distributions (RMD) kick in. How so?

Some retirees may find they have so much saved in tax-deferred retirement accounts that combining RMDs with other sources of income—such as Social Security benefits and interest, dividends, or capital gains from brokerage accounts—could move them into an unexpectedly high tax bracket. Not only could this lead to a larger tax bill, but it could also mean assets won't last as long.

Let's take a look at how you can estimate your RMDs and some strategies you can consider to help reduce the impact of your distributions on your tax return.

How is your RMD calculated?

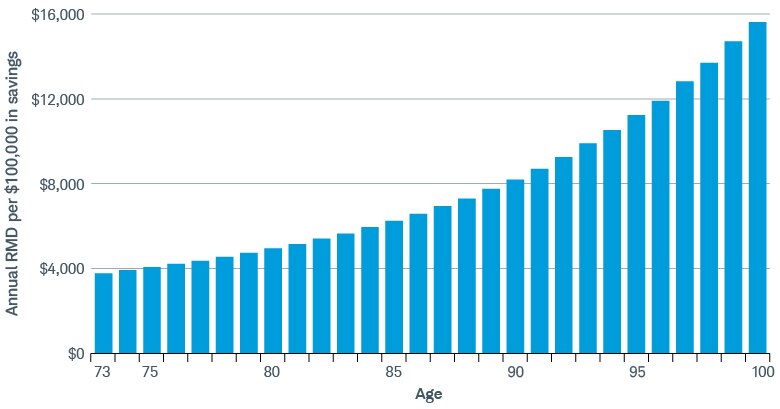

The IRS calculates RMDs by taking the balances of your tax-deferred retirement accounts at the end of the prior year and dividing the total by a number based on your life expectancy factor (see "A step-by-step guide to calculating your RMD"). The denominator gets smaller as your age increases, meaning the minimum amount of your distributions gets larger as time goes by. For example, for those age 73 taking their first RMD, the denominator starts at 26.5—or about $3,774 for every $100,000 in the account. But if you're age 93, the denominator becomes 10.1, which means your RMD jumps up to about $9,901 for every $100,000 in that account.

RMD amounts change over time

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research and the IRS.

For illustrative purposes only. Individual situations will vary and are not the experience of any specific clients.

Many IRA custodians will notify account holders of their RMD amount each January, but you're ultimately responsible for ensuring the calculation is correct. Typically, you have until December 31 to take your full distribution—or if you're taking your first RMD, April 1 the following year.

Take note that if you decide to delay your initial distribution until April, your second RMD will be due on December 31 of that year as well. Two sizable, taxable withdrawals in the same tax year can more easily bump you into a higher bracket, so it's often best to take your first distribution in the calendar year that you reach your RMD age.

Once you start withdrawing funds, you should remain vigilant because your account balances will continue to fluctuate—and with them your RMDs.

A step-by-step guide to calculating your RMD

- Determine the balance of each tax-deferred retirement account as of December 31 of the previous year.

- Find the distribution period that corresponds to the age you'll turn this year.

- Divide the account balance for each account by the distribution period to determine your RMD for each account. (The IRS permits you to aggregate your RMD amounts for all your IRAs—including SIMPLE IRAs and SEP IRAs—and withdraw the total from a single IRA account. You may also aggregate RMDs for 403(b) accounts, but this rule doesn't apply for most defined contribution plans, such as 401(k)s.)

| Age | Distribution period (DP) |

|---|---|

| 73 | 26.5 |

| 74 | 25.5 |

| 75 | 24.6 |

| 76 | 23.7 |

| 77 | 22.9 |

| 78 | 22.0 |

| 79 | 21.1 |

| 80 | 20.2 |

| 81 | 19.4 |

| 82 | 18.5 |

| 83 | 17.7 |

| 84 | 16.8 |

| 85 | 16.0 |

| 86 | 15.2 |

| 87 | 14.4 |

| 88 | 13.7 |

| 89 | 12.9 |

| 90 | 12.2 |

| 91 | 11.5 |

| 92 | 10.8 |

| 93 | 10.1 |

| 94 | 9.5 |

| 95 | 8.9 |

| 96 | 8.4 |

| 97 | 7.8 |

| 98 | 7.3 |

| 99 | 6.8 |

| 100 | 6.4 |

| 101 | 6.0 |

| 102 | 5.6 |

| 103 | 5.2 |

| 104 | 4.9 |

| 105 | 4.6 |

| 106 | 4.3 |

| 107 | 4.1 |

| 108 | 3.9 |

| 109 | 3.7 |

| 110 | 3.5 |

| 111 | 3.4 |

| 112 | 3.3 |

| 113 | 3.1 |

| 114 | 3.0 |

| 115 | 2.9 |

| 116 | 2.8 |

| 117 | 2.7 |

| 118 | 2.5 |

| 119 | 2.3 |

| 120 and over | 2.0 |

For example, let's say you're 85 and not married. You had a total of $2 million in your tax-deferred IRAs at year-end of last year. Your distribution period is 16.0, which means your RMD for this year will be $125,000 ($2,000,000 ÷ 16.0).

If you miscalculate your RMD or fail to withdraw the full amount on time, you'll owe up to a 25% tax penalty on the amount not taken—10% if you withdraw the remaining RMD within two years.

Calculate your RMD

Use Schwab's online calculator to estimate your annual distributions.

Strategies to manage RMDs

If you're concerned that RMDs could push you into a higher tax bracket, you may want to explore some strategies that could potentially reduce your tax-deferred balances and lower your future RMDs. Here are three options to consider.

1. Begin taking withdrawals at age 59½

One approach is to start withdrawing funds from tax-deferred accounts at age 59½—generally your earliest opportunity without incurring a 10% penalty. To avoid pushing yourself into a much higher tax bracket, typically it's best to target a specific tax rate for your distributions. One way to do this is by using a proportional withdrawal strategy, where you take money from both your taxable brokerage accounts and your tax-deferred accounts at the same time.

This strategy can reduce the overall size of your tax-deferred accounts—and with them, your future RMDs. Such withdrawals can also help make it possible to defer claiming your Social Security benefit, which increases 8% for every year you wait to collect beyond your full retirement age (up to age 70, after which there is no incremental benefit for delaying).

However, drawing down your account balance at an early age means you could lose out on years of potential growth of the withdrawn funds, so be sure to work with a financial planner to determine if the tax savings from this strategy can offset that growth.

2. Convert to a Roth account

A second strategy is a Roth conversion, where you rollover holdings in your tax-deferred accounts to a Roth account, which is exempt from RMDs.

There are several situations in which such a conversion may make sense:

- You believe you'll be in a higher tax bracket when you eventually withdraw the money.

- You want to manage or reduce distributions once you hit your RMD age.

- You want to leave your heirs an income-tax-free asset, as Roth withdrawals aren't subject to income tax, assuming you've met the appropriate 5-year rules.

Does converting to a Roth IRA make sense for you?

Use Schwab's Roth IRA conversion calculator to compare the estimated future values of keeping your traditional IRA versus converting it to a Roth, as well as calculate the taxes you'd owe on a Roth conversion.

And remember to consult a qualified wealth manager or tax professional before making any decisions.

3. Make a qualified charitable distribution

If your charitably inclined and have reached age 70½, a third option to reduce or entirely satisfy your RMDs opens up: a qualified charitable distribution (QCD), in which funds are transferred directly from an IRA to a qualified charitable organization. Unlike RMDs, QCDs are not taxable, and each individual can donate up to $111,000 from their IRA for tax year 2026. (QCD limits are indexed for inflation every year.) You may also direct a one-time $55,000 QCD, which will count toward your annual limit, to a charitable remainder trust or charitable gift annuity in 2026.

Before making a QCD, there are a couple of caveats:

- Your IRA custodian must transfer the funds directly—and only to a 501(c)(3) organization (donor-advised funds and most private foundations aren't eligible).

- You can't claim the QCD as a charitable deduction, but the distribution doesn't count as taxable income either.

A QCD can make a lot of sense if charitable giving is already part of your overall financial plan. You get the satisfaction of helping a worthy cause, while also covering a portion or all of your RMD by year-end.

Putting the RMD tax puzzle together

Given the complexities of RMD rules and the tax strategies involved with the options mentioned above, it's best to consult with a qualified tax advisor or a wealth manager who can help you navigate the intricacies of taking your distributions during retirement.