Shorting Stocks in Your Investment Strategy

There's a straightforward strategy for making money when the market is going up: buy. When a stock, sector, industry, or the broader market enters a short-term correction or a longer-term bear market, strategies for making money become complicated.

A key bear-market strategy is short selling, which looks to profit from stocks that decline in value. Selling short is risky, however, because there's no guarantee the stock price will go down—and it could in fact go up.

It also involves a few more steps than buying a stock. But for those who are comfortable with risk, short selling creates an opportunity to profit from a market decline. So, if you're new to the idea of shorting stocks as part of an investment strategy and would like to learn more, start by exploring the basic mechanics of a short sale.

How does short selling work?

Shorting a stock is the opposite of being "long," which means to own an asset. The basic principle underlying investments in long stock is to buy low and sell high. A short sale works backward: sell high first, and (hopefully) buy low later. But how can you sell a stock that you don't already own? You borrow it.

A trader who believes there will be a market downtrend might borrow shares of a stock through their broker and sell them, in the hope of buying back the shares at a lower price to repay the loan. If the share price declined by the time the trader repurchased the stock, the difference in price is their profit minus any transaction costs.

However, there's potentially unlimited risk with the trade. If the stock rises instead of declines, the trader may need to repurchase the shares for more than they sold them, resulting in a loss. The higher the stock rises, the worse the potential loss.

In addition to its risks, short selling carries a stigma too. After all, a short sale generates profit from a company's partial or total decline, and not everyone is comfortable with that. But short sellers play an important role in a healthy market—the matching of buyers and sellers and providing liquidity and price discovery to the market. The best short sellers do careful research and bring any beliefs they have about excess enthusiasm, inflated valuations, or other potential issues to the market by shorting shares.

Short selling is available only to investors with margin trading privileges because it involves borrowing. It's only appropriate for those who are comfortable with the inherent risks. To sell short, work with your brokerage firm to borrow shares from another investor and then sell those. Here's an example.

Shorting a stock: A hypothetical example

Suppose there's a stock trading at $40 that you believe to be overpriced, and you'd like to go short to take advantage of a potential move to the downside.

- You place an order to sell short 100 shares of stock XYZ at the price of $40.

- Your broker borrows the shares, fills your order, and places them in your account; you're now net short $4,000 worth of XYZ stock (100 shares at $40 = $4,000).

Favorable scenario:

Stock XYZ falls in price to $35.

You sold at $40 and decide to capture the profit. You buy at $35 to close your position, pocketing the difference of $500 (100 shares at $5) minus any transaction costs.

A word on dividends: If the company paid any dividends during the time you were short, your account would be reduced by the amount of the dividend. Why? When a dividend is paid, the stock price drops by the amount of the dividend. For example, if a stock is at $40 and the company pays a $1 dividend, the owner of record gets the $1, and the stock value is reduced, all else equal, to $39. So, if you held a short position on the ex-dividend date, you'd get the benefit of the stock drop, but you'd essentially pay the dividend.

Not-so-good scenario:

Stock XYZ rises by $5 to $45.

This position has moved against you because you sold short at $40 and now have to buy it back at a higher price. You decide to buy at $45, losing $500 (100 shares at $5) plus any transaction costs as well as any dividends you might have paid along the way.

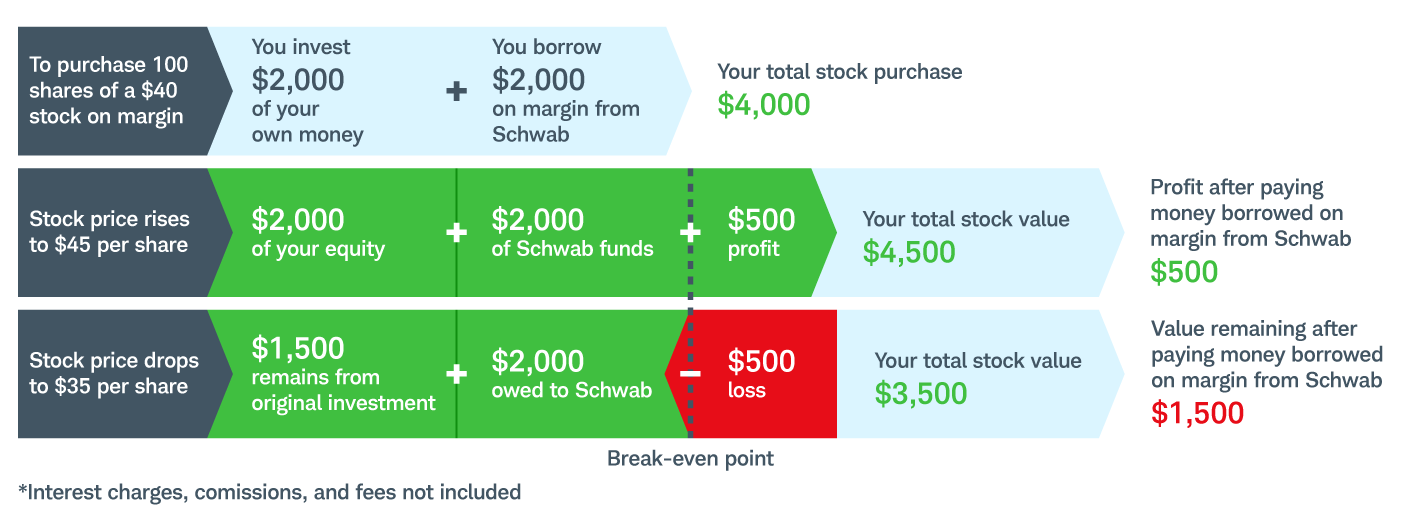

To sell stocks short, you need to open a margin account

A margin account allows you to borrow shares or money to increase your buying power. In this case, you can sell short marginable stock with up to twice the buying power of a traditional cash account. The securities you hold in your account act as collateral for the loan, and you pay interest on the money borrowed.

To qualify for a margin trading account, you need to apply, and you must have at least $2,000 in cash equity or eligible securities.

When you use margin, you must maintain at least 30% of the total value of your position as equity at all times. (Keep in mind, some stocks have higher margin requirements, and so do some customers.) If market fluctuations reduce the value of the equity in your account, your broker will issue a margin call, which you must meet by adding funds to your account. If you fail to meet a margin call, your broker will buy back your short position, closing your trade at a loss.

For illustrative purposes only.

Margin accounts and margin trading can be risky, so it's important to understand the risks before you jump in. If you're interested in applying for margin trading privileges, log in to your account. On Schwab.com, from Profile, select Margin & Options and look for Apply for margin, where you can read the disclosures and request margin trading. Once the application is approved, you can tap into your available funds at any time by placing a trade.

Potential benefits and risks of short selling

Short selling techniques give you some powerful tools:

- Profiting from downturns. Short selling allows you to seek positive returns during a market downturn.

- Hedging your long positions. You can use short selling to hedge stocks you already own. For instance, you can short a sector exchange-traded fund (ETF) to help hedge a number of related sector stocks that you may be holding in your portfolio.

- Playing both sides of the market. You can consider going long on stocks you expect to outperform while going short on stocks that you expect to underperform. You could even consider buying (going long) and selling (going short) two highly correlated stocks that have moved far apart and that you expect to converge.

- Diversifying a portfolio. If a portfolio is completely made up of long positions, a margin account could allow you to further diversify in a market downturn (what's known as systematic risk) by having both long and short positions. Also, if your portfolio is dominated by a large position in one stock, a margin account could allow you to diversify your portfolio without having to sell your current stock. This strategy can be particularly helpful if you have a large unrealized capital gain and want to try to keep it that way.

But shorting carries risks:

- Unlimited risk. Because there is technically no limit to how high a stock or ETF price can rise, your risk of loss in short selling is unlimited.

- Dividends and other payments. You're responsible for any dividends, stock splits, or spin-offs paid on the borrowed stock as well as potential interest costs on hard-to-borrow securities.

- Unfavorable liquidation. To maintain margin in your account, you may be required to close your short positions at unfavorable prices, particularly in cases where your stock experiences a sharp surge in price.

- Historical upward trend. Historically, the broader stock market has risen over time. Though past performance is no guarantee of future results, the market's tendency to rise over time remains a potential risk for any short seller.

Bottom Line

With proper risk management techniques, shorting stocks can potentially enhance your investment strategy by hedging stocks and adding diversification to your portfolio. But it isn't for every investor, especially those who don't want to face its unlimited risk.