Straddles vs. Strangles Options Strategies

Traders new to options strategies typically begin with the basic call and put strategies—selling covered calls for potential income and buying puts for temporary downside protection. Although many traders never venture beyond the basics, some traders look at the versatility and flexibility of advanced options strategies and move to strategies that can potentially help them with pinpointed objectives.

When qualified traders begin to move towards more advanced strategies, it's important they consider the greater risk potential that comes with these advanced trades. It's also important for traders to remember that with these more complex strategies, understanding what trades can do under different conditions also becomes important.

What are long straddles and strangles?

Traders use long straddle or strangle option strategies when they expect an underlying stock to make a substantial move higher or lower, but they aren't sure on direction. For example, perhaps there's an earnings report coming up on a stock you're following. Or maybe there's a product launch on tap and you're not sure how it will impact the stock price. One way or the other, you believe an increase in volatility could be on the way.

The two strategies—long straddles and strangles—can potentially offer exposure to future volatility in situations when the trader anticipates a substantial move in the underlying stock. A long straddle involves buying a call and a put on the same underlying security with the same strike prices and the same expiration dates, whereas a long strangle involves buying a call and put with the same expiration on the same underlying security but with different strike prices.

Long straddles vs. strangles: directionally agnostic

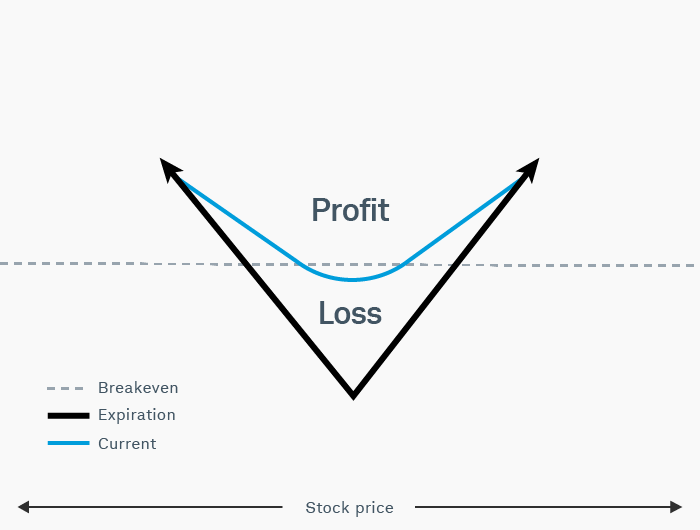

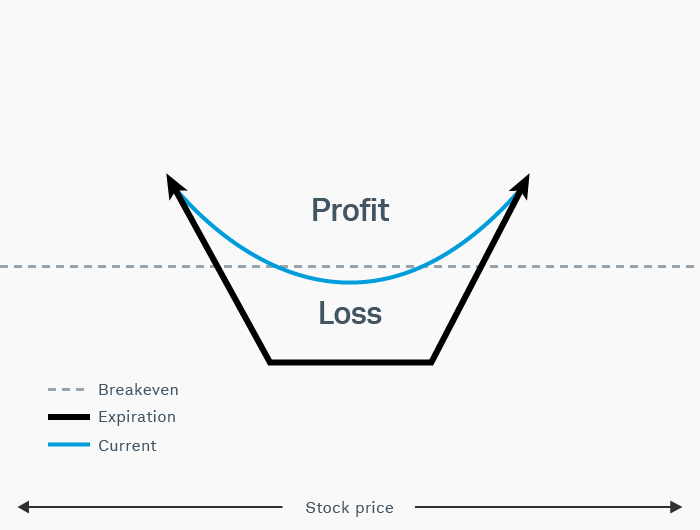

Long straddle and strangle options strategies are considered "directionally agnostic," meaning the magnitude of a move, not the direction, often determines the outcome of the trade. Both are debit trades, meaning the trader pays a premium (plus any transaction fees) to enter the position. The figures below show the risks and reward possibilities at expiration and illustrate how both strategies are profitable if the underlying stock moves sufficiently higher or lower. In other words, the ideal outcome is for either the put or call to increase in value and more than offset the initial debit.

The point of maximum loss for the long straddle is at the strike price because, if both options expire at-the-money1 (ATM), both the put and call will likely expire worthless. Similarly, if the stock is between the two strikes of the long strangle, the options will likely expire worthless, and the debit is lost. Note that, if either of the contracts is in-the-money (ITM) and the position is held through the expiration, it can result in automatic exercise. The broker may or may not, at its discretion and without obligation or notification, issue a Do Not Exercise (DNE) if the account is not sufficiently funded to cover the sale (upon the exercise of the put) or the purchase (on the call) of the resulting underlying shares.

Excluding transaction fees, both the long straddle and strangle have two break-even points at expiration. For the long straddle, the break-evens are computed as the strike price minus the debit and the strike price plus the debit. On the long strangle, the break-evens are the lower strike minus the debit and the higher strike plus the debit. For the trades to be profitable at expiration, the underlying stock must be below the lower break-even or above the higher break-even. Many traders prefer to close the position (or either the puts or calls) prior to the expiration and the profit or loss will depend on whether the premium collected is greater than the initial debit. However, there's no guarantee that an option can be closed before expiration if it has little or no value remaining.

Risk profiles for long straddles and long strangles

For illustrative purposes only.

For illustrative purposes only.

Choosing between long straddles and strangles

So, how does a trader choose between the long straddle or the strangle? The answer, as is often the case with options strategies, is that it depends on the trader's objectives and risk tolerance. In general, a long straddle will cost more, but the chance of a 100% loss only occurs if the underlying stock is exactly equal to the strike price at expiration. Conversely, the long strangle is generally less expensive to buy, as its legs consist of out-of-the-money (OTM) options, but the long strangle has a greater chance of losing 100% because both options will expire worthless if the underlying stock is between the two strike prices at expiration.

Let's look at an example.

Using the 70-strike options prices in the table below, a trader could buy the straddle for $2.80 ($1.40 for the call and $1.40 for the put), plus transaction fees. At expiration, if the stock is either higher or lower than $70 by more than $2.80, then the straddle would in theory be profitable. A strangle example could be the 68 put and the 72 call. Buying the strangle would cost $1.40—half of what the straddle cost (again, plus transaction fees). With this lower cost, though, comes the need for the stock to move more to make the strangle profitable. At expiration, not including transaction fees, the stock would need to be below $66.60 ($68 – $1.40) or higher than $73.40 ($72 + $1.40). This example does not take volatility into consideration. Read on to see how implied volatility (IV) can impact a long straddle and strangle.

- Stock price = $70

- Call bid

- Call ask

- Strike

- Put bid

- Put ask

-

Stock price = $7025 days until expirationCall bid2.65Call ask2.80Strike68Put bid0.65Put ask0.75

-

Stock price = $70Call bid2.05Call ask2.15Strike69Put bid1.05Put ask1.10

-

Stock price = $70Call bid1.35Call ask1.40Strike70Put bid1.35Put ask1.40

-

Stock price = $70Call bid0.90Call ask0.95Strike71Put bid1.85Put ask2.00

-

Stock price = $70Call bid0.60Call ask0.65Strike72Put bid2.50Put ask2.70

The risks of long straddle and strangle options strategies

Options typically don't need to be held through expiration. Many traders will look to close their long straddle or strangle once the date of the anticipated move has passed. By owning a straddle or strangle, you have two options, both subject to time decay ("theta"), which is the natural daily erosion of options prices. One risk of buying a straddle or strangle is that the magnitude of price movement in the underlying stock may not be enough to compensate for the theta.

Also, the higher the IV as you enter the trade, the higher the entry price point for your long straddle or strangle, and thus the greater the price move a trader may need to see in the underlying before the trade breaks even. Computed using an options-pricing model, IV is expressed as a percentage and reflects the market's perception about the potential volatility of the underlying stock in the future.

How can a trader determine whether a stock's IV is high or low? One way is to use the IV Percentile, available on the thinkorswim® platform under the Trade tab > Today's Options Statistics. The IV percentile indicator compares the current IV to the 52-week high and low. The larger the IV percentile, the higher the current IV relative to values over the last year. However, high IV doesn't necessarily mean the long straddle or strangle is too expensive to consider. On the other hand, simply because IV is low relative to the past doesn't mean the long straddle or strangle is a bargain. Because markets are forward-looking, implied volatility and option premiums are often changing based on expectations about the future volatility of the underlying stock.

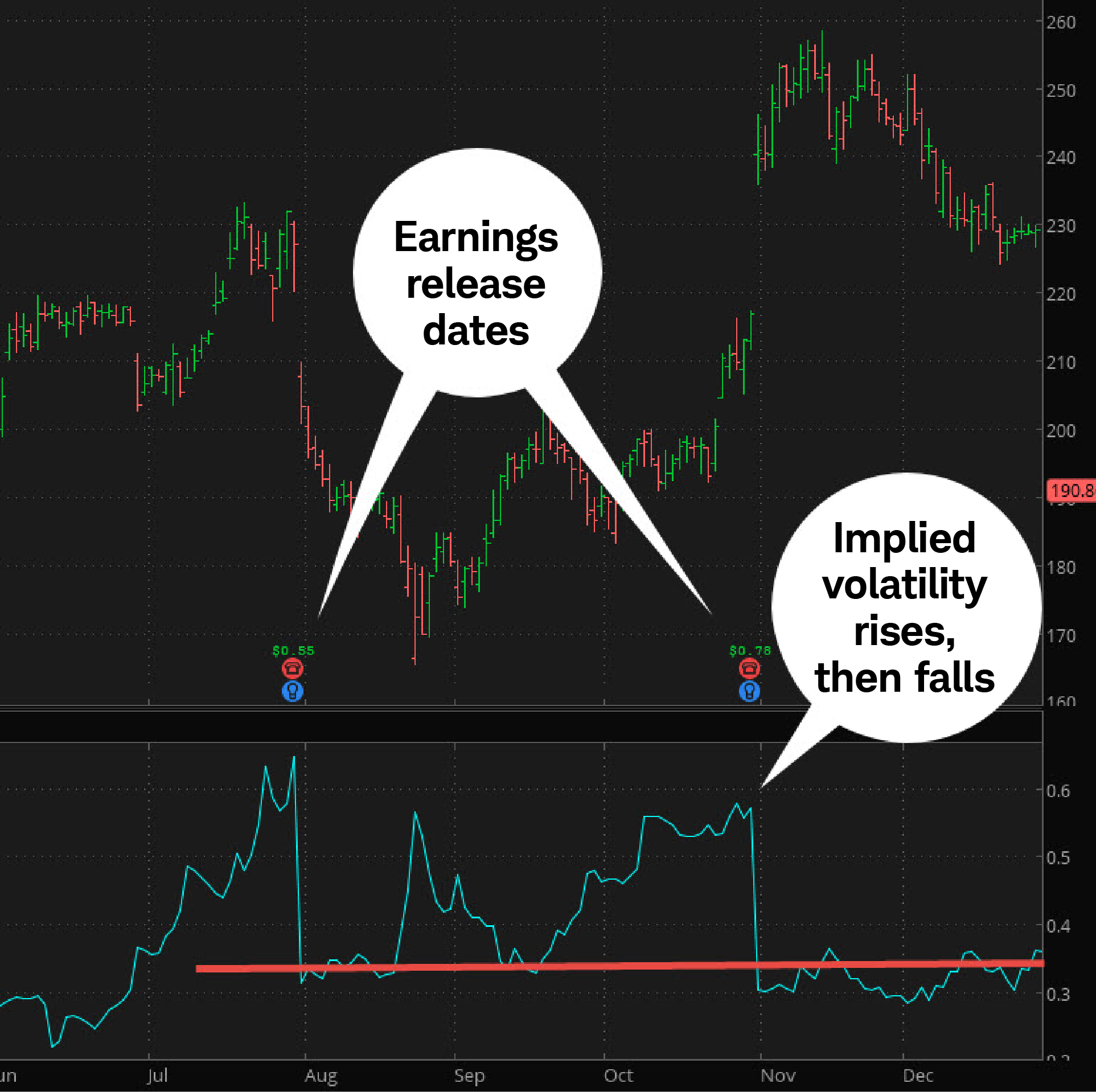

Post-earnings IV

Holding on to a long straddle or strangle through earnings (or other widely anticipated events) can potentially be a double-edged sword. Sure, you're looking to capitalize on the big move, but typically once the event has passed and the stock has its move one way or the other, IV and the option premiums tend to fall. So, before considering a long straddle or strangle ahead of an event, traders typically assess the impact of time decay and implied volatility. For example, after an earnings report, it's not uncommon to see IV fall sharply. Traders call it a "volatility crush". See the figure below.

Implied volatility falling after an earnings release

Source: thinkorswim platform

Straddles and strangles: The long and short of it

Long straddles and strangles can be used to target directionally agnostic movement. But it's not enough to simply have the underlying stock move; the movement has to be enough to overcome options decay, the potential of which is reflected in the options price at the time of entry. However, given sufficient magnitude, long straddles and strangles options strategies can become profitable irrespective of direction.

Of course, the opposite is also true. Think IV is too high and poised to come down? Or think the underlying is liable to sit still for a while and you'd like that theta to act as a tailwind instead of a headwind? Flip the risk profiles of the long straddle and long strangle upside down and they're what a short straddle and strangle look like. But notice that, with the long strategies, the profit potential is unlimited. With the short strategies the potential for loss is unlimited.

How to approach earnings reports can depend a lot on a trader's market views, objectives, and risk tolerance. Options straddles and strangles can be an effective way to trade volatility, but make sure you know and are comfortable with the risks involved before applying these trading strategies to any trade.