Theta Decay in Options Trading

Many basic options strategies often aim to profit from price fluctuations in the underlying security. A trader who buys a call option, for example, is hoping the price of the underlying will rise, increasing the value of their option. However, some strategies seek to profit not from movement in the underlying asset's price but from a unique trait of options: Their inevitable decline in value over time. This trait is known as theta, or time decay, and it's the reason options are considered "wasting" assets.

There are many well-known strategies—like covered calls and cash-secured puts—where traders sell options to benefit from time decay. But in this article, we'll walk through a few more advanced theta-based strategies. Qualified traders who decide to use these strategies should ensure they understand the mechanics and greater risk potential involved before placing a trade.

Reviewing the greeks

Before jumping in to some of the more complex strategies traders use to potentially profit from time decay, a review of the options greeks is beneficial. These risk metrics are computed using an options-pricing model and can help quantify the relationship between the price of an option and time, implied volatility, and changes in the underlying asset's price. Here are the main greeks:

- Theta (or time decay) is the expected decrease in the price of an option each day as it approaches expiration. Note: Although theta is the theoretical daily time decay, in practice, the time decay of an option generally follows a non-linear, accelerating curve, giving it a hockey stick shape when graphed.

- Delta measures how much the price of an option is expected to change for every $1 move in the underlying asset's price.

- Gamma gauges how much delta will change for every $1 movement in the underlying asset's price.

- Vega measures how a 1% change in the underlying asset's implied volatility will affect the price of an option.

How does time decay (theta) work?

Theta represents the inevitable loss of value in an option over time. While conceptually straightforward, its practical application is worth reviewing.

When a trader buys an option, even if its "intrinsic value" goes up, the "extrinsic value" of that option will decrease over time. Put another way, the theta value of that option is negative. This is because, with less time, the statistical probability that an underlying asset's price will move enough for an option to become profitable decreases. As a result, with all else equal, the rate at which the value declines in a long option will accelerate the closer it gets to expiration.

However, when shorting options, traders attempt to profit from the passage of time. Put another way, short options have positive theta. To better understand this concept, it's important to review the intrinsic and extrinsic value of an options contract.

Intrinsic and extrinsic value and the dynamics of options theta

Intrinsic value is the difference between the underlying asset's price and the strike price, or the amount the option would be worth if it were exercised today. Extrinsic value is the difference between an options premium and its intrinsic value. Essentially, it represents the portion of the value of an option that is derived from external factors rather than its inherent worth.

At expiration, an option has no extrinsic value because external factors—like time to expiration, implied volatility, interest rates, or dividends—are no longer impacting its price. This is why many option traders refer to extrinsic value as "time value" or "time premium."

The expected daily value loss of an option due to time decay (theta) is also heavily dependent on its moneyness, defined as:

- At-the-money (ATM) options have strike prices at or very near the underlying asset's price.

- Out-of-the-money (OTM) call options have strike prices above the underlying asset's price, while OTM put options have strike prices below the underlying asset's price.

- In-the-money (ITM) call options have strike prices below the underlying asset's price, while ITM put options have strike prices above the underlying asset's price.

The value of ATM options decays the fastest over time (all else equal) because these options have the most uncertainty about whether they will close OTM or ITM and therefore the most extrinsic value. The value of ITM and OTM options, on the other hand, decays more slowly (all else equal) because they have less extrinsic value. The further out of the money an option is the lower its extrinsic value and thus the slower its value will decay over time—until it nears expiration.

The value of shorter-term options also decays faster than longer-term contracts' value (again, all else equal), and the rate of their value decay speeds up as they get closer to expiration. It's these traits that traders put to work when seeking to profit from theta using advanced options strategies.

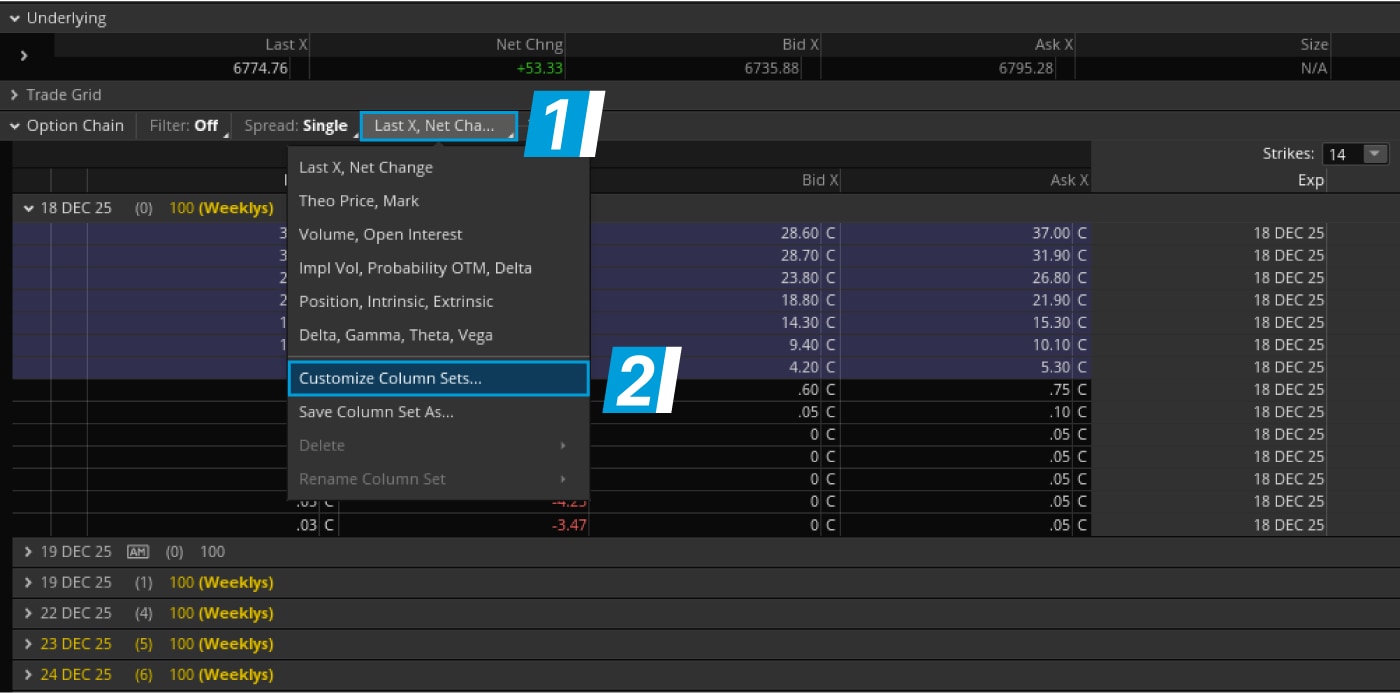

Where to find theta on thinkorswim

On the thinkorswim® platform, traders can easily set up an Options Chain to display the greeks, including theta. To start, select any of the column headers below the Calls or Puts sections. A drop-down menu will appear. Select Option Theoreticals & Greeks, then Theta.

Short call vertical

Source: thinkorswim platform

For illustrative purposes only.

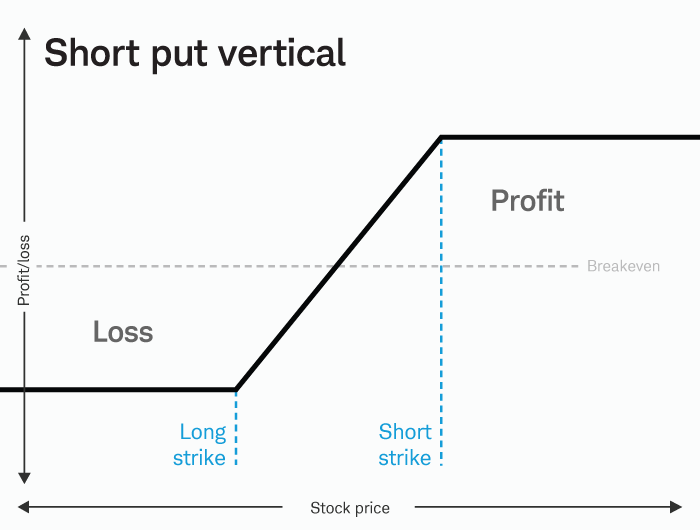

Short put vertical

Source: thinkorswim platform

For illustrative purposes only.

Three (mostly) theta-based options strategies to consider

Now that we've reviewed how theta works and where to find it on thinkorswim, let's break down a few advanced options strategies that attempt to profit from time decay.

Note: Other greeks play a part in how options prices change, but we'll assume everything remains equal for the purpose of these examples.

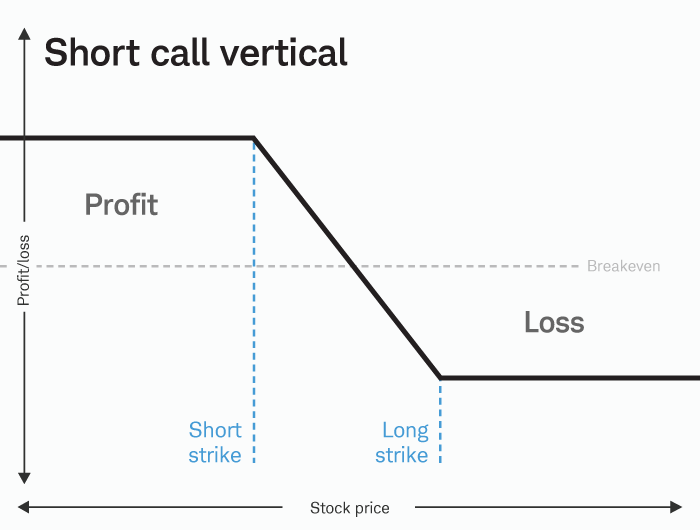

Strategy #1: Short OTM vertical spread

For illustrative purposes only.

A short iron condor is a four-legged spread made up of a short OTM call vertical spread and a short OTM put vertical spread, both with the same expiration dates. Typically, both vertical spreads are OTM and are centered around the current price of the underlying asset.

But unlike the individual vertical spreads themselves, the directional bias of an iron condor is neutral (see risk profile below). The best-case scenario occurs when the underlying asset's price stays between the two short strikes until expiration, at which point both vertical spreads expire worthless and the trader keeps the initial credit. Maximum loss occurs if the underlying asset moves outside the long strikes of the short call or short put spreads. This loss is calculated as the distance between the strikes of the vertical spread minus the initial credit received from selling the iron condor (not including transaction costs).

The iron condor capitalizes on theta similarly to short OTM vertical spreads because it is simply the combination of a put and a call OTM vertical spread.

Strategy #2: Short iron condor

Note that when trading vertical spreads and iron condors, the strikes are all within the same expiration dates, targeting points of maximum theta by positioning short strikes closer to the money than the long strikes. Calendar spreads, however, leverage a different aspect of theta—its acceleration as expiration nears.

A calendar spread involves selling one option (a call or a put) with a near-term expiration date and purchasing the same option type at the same strike price but with a later expiration date. The goal is to capitalize on theta's faster erosion in the near-term short option compared to the later-dated long option. Then, the trader can either close the position (if there is sufficient liquidity)—profiting from the difference between the initial debit paid and the remaining value of the spread—or they can potentially roll the spread to a later date.

Calendar spreads are also defined-risk strategies, with maximum risk typically limited to the initial debit paid for the spread. The best-case scenario occurs when the underlying is right at the strike price as the short-term option expires (see risk profile below). The worst-case scenario, however, occurs when the underlying asset moves significantly away from the strike price at the short-term option's expiration. In this case, the loss would be the debit paid for the calendar spread plus any transaction costs.

Strategy #3: Calendar spread

For illustrative purposes only.

When trading calendar spreads, careful trade management is required as the near-term option approaches expiration. While short options can be assigned at any time (when American-style option settlement applies), they are more likely to be assigned if they are closer to ITM. When the short option expires (whether ITM or OTM), the later-dated option remains, effectively becoming a long single-leg option.

Many traders opt to liquidate or roll a calendar spread at least a few days before the first expiration date. However, keep in mind that closing or rolling the position will entail additional transaction costs, which may affect any potential return. Should the short option be assigned at or before expiration, the resulting position would be the later-dated option plus long or short 100 shares of the underlying asset. This could significantly change the delta exposure of the original calendar spread and require trade management.

Bottom line

Although each of the above strategies involves long options that experience time decay, a successful trade assumes the short options generate enough premium to offset (and exceed) what the long options lose. But if there's an adverse move in the underlying asset, such as a short OTM vertical spread moving ITM, then the net time decay of the trade can work against the trader. Similarly, in the case of a calendar spread, if the implied volatility of the front leg were to rise relative to the implied volatility in the later-dated leg (all else equal), the spread price could go against the trader.

Ultimately, strategies that seek to profit from the inevitable decay in the value of an option are one way option traders put time on their side and potentially have it work in their favor. However, keep in mind, these are advanced options strategies that require a thorough understanding of the risks and active trade management.