3 Reasons to Consider Putting Your Cash to Work

Cash serves a valuable role in many investors' portfolios. It can pay the bills and fund short-term goals—a key reason it's important to keep enough cash around to meet your immediate needs.

You don't want to take investment risk with money you need soon, but cash and cash investments—beyond money you've set aside for spending right away—can be a part of your portfolio as well. Cash, both for savings and expense management and for investing, can help you play defense during market downturns by reducing the impact of market volatility on your returns.

But cash isn't always king, depending on why you hold it. Sometimes our emotions enter the picture and hold undue sway over our investing decisions. Loss aversion—where the pain of loss is felt more strongly than the pleasure of an equivalent gain—is a real phenomenon and can manifest itself in a number of ways.

For some, it might mean cashing out of investments to avoid losses when the going appears to be getting tough. Others could be avoiding (or not allocating enough) to stocks and other assets that could potentially earn more over time. The result can be a cash-heavy portfolio, which can have a downside. The key is the right balance, for your time horizon and needs.

In this article, we look at three reasons you should consider putting your cash to work.

1. Cash generally loses purchasing power when you factor in inflation

The value of every dollar you hold fluctuates as the broad level of prices (i.e., inflation) rises and falls. Inflation tends to increase over time, which means the dollar you held a year or two or three years ago won't buy as much today.

That loss in purchasing power can add up meaningfully over time. By not investing in stocks or higher-yielding investment-grade bonds, your money doesn't have the potential opportunity to earn interest or grow. Consider what happens when inflation averages out at 3%.

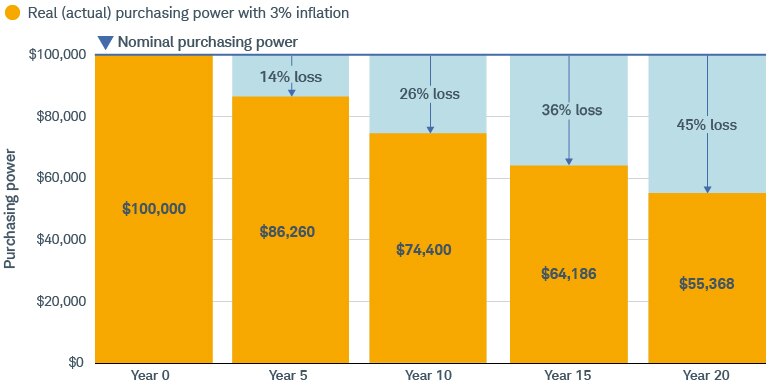

Inflation can severely erode purchasing power over time

A person who has $100,000 sees the real purchasing power of that money shrink to $74,400 after 10 years and all the way down to $55,368 after 20 years. In this case, a portfolio made up entirely of cash still loses value—and lots of it—declining 26% by year 10 and by 45% by year 20.

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research.

The "nominal" amount is the stated value. The "real" amount is the value adjusted for the effects of inflation. Inflation is represented by the change in the Consumer Price Index for AII Urban Consumers (CPI-U). From 01/01/2005 to 01/01/2025, inflation averaged 2.6%. But during some periods in the past, the average was much higher: It averaged 6.2% from 1970–1989 and 5.0 from 2021–2024¬. For illustrative purposes only.

It's important to understand the effects of inflation because it decreases the amount of goods or services you can buy (purchasing power), all else being equal.

2. Short-term investments can undercut your earning potential

You can allocate your cash in short-term investments to try to keep up with the pace of inflation, but your earning potential is heavily influenced by the current level of interest rates. This might make sense when interest rates are high, but low rates can suppress returns on interest-bearing savings accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), and money market accounts—all popular vehicles for investing short-term assets.

Instead of putting all your cash in short-term investments, maximize what you can afford to invest in assets with a potential for higher returns over time, such as stocks and intermediate- or long-term investment-grade bonds. Consider the hypothetical example of two people—Alexis and Diego—who both inherited $200,000 in 2005. To illustrate the point, let's factor out inflation and assume that neither withdraw any of their inheritance.

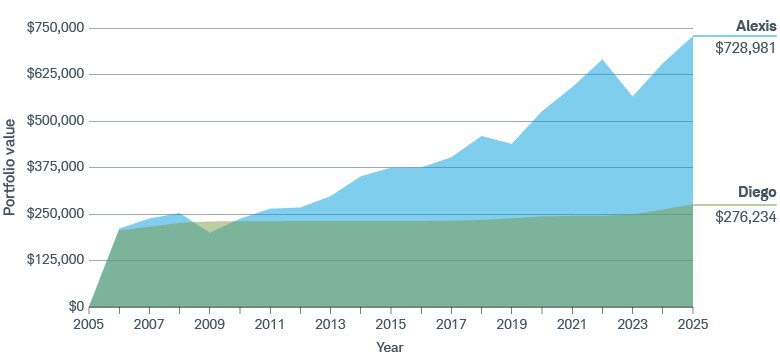

Investing can have greater potential growth compared to saving

Diego deposited his funds in a bank account, earning an annual average of a little more than 1% over 20 years. Alexis invested her $200,000 in a moderate-risk portfolio, which returned an average of almost 7.24% over the same time. In return for taking on more risk, Alexis ended up with $728,981 compared to Diego's $276,234.

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research. Data from 01/01/2005 to 01/01/2025.

The moderate model portfolio (allocated 35% large-cap stocks, 35% fixed income, 15% international stocks, 10% small-cap stocks, and 5% cash investments) is not suitable for all investors. Returns assume reinvestment of dividends and interest. Fees and expenses would lower returns. This chart represents a hypothetical investment and is for illustrative purposes only. The actual rate of return will fluctuate with market conditions. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

That said, short-term investments are a smart way to hold cash you need to cover emergencies and near-term expenses. For non-retirees, that means setting aside three to six months' worth of essential living expenses in a relatively safe, liquid account, such as an interest-bearing checking account or money market fund. Retirees, on the other hand, can avoid selling investments at a loss during a downturn by keeping one year's worth of expenses in cash reserves and two to four years' worth in more conservative investments, like short-term bonds.

3. Overallocation to cash can limit your opportunities for growth

Moving to a higher cash allocation is a lever that investors often pull when they believe they need protection against significant losses or liquidity to fund an upcoming expense (e.g., a college education or home purchase), but some go too far in liquidating their higher-yielding assets—particularly during market volatility. Schwab's most conservative model portfolio allocates 30% to cash investments, with the balance split between 50% fixed income assets and 20% in equities.

If you're considering ever increasing your cash allocation beyond this threshold, it's wise to keep three things in mind:

- It's difficult to time the market consistently and successfully. Research conducted by Schwab shows that the cost of waiting for the perfect moment to invest typically exceeds the benefit of even perfect timing.

- Cash has historically underperformed other asset classes. The difference in performance can be significant over time, especially relative to returns for small- and large-cap stocks, international stocks, and bonds.

- When investing your cash, balance the risk and return. The percentage of cash investments in your portfolio—such as high-yield checking or saving accounts, money market funds, or certificates of deposit—could range from 5% (for younger, more aggressive investors) to 30% (for those who need the money soon, have little tolerance for risk, or are relatively far along in their retirement). Any cash exceeding those amounts could be invested for potential growth and higher income.

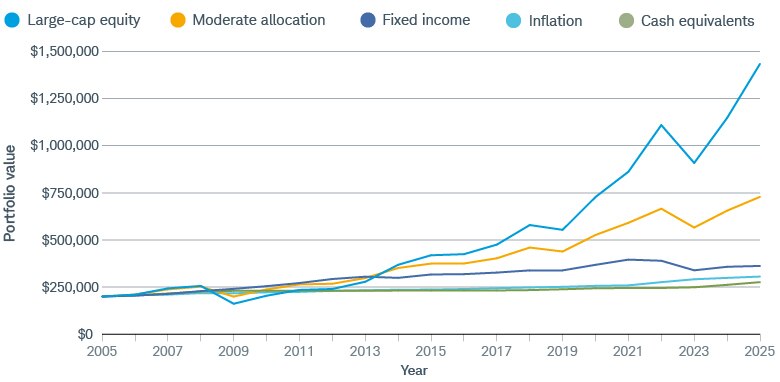

Portfolio value by investment type compared to inflation

Over a 20-year time horizon from January 1, 2005, to January 1, 2025, the performance of $200,000 invested in a large-cap equity, a moderate portfolio (35% fixed income, 35% large-cap equity, 15% international equity, 5% small cap equity, and 5% cash investments), and fixed income assets experienced higher growth than a portfolio kept in cash and cash equivalents. The all-cash portfolio was also valued lower than the buying power of $200,000 adjusted for inflation—that is, the amount needed at the current inflation rate to purchase the equivalent value of goods or services in 2005.

Source: Morningstar, Inc. Based on the copyrighted works of Ibbotson. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

The chart illustrates the growth in value of $200,000 invested in various financial instruments from 1/1/2005-01/01/2025 Results assume reinvestment of dividends, capital gains, and coupons and no taxes or transaction costs. Generally small-cap stocks are in the bottom 50% of publicly traded companies based on market capitalization. These stocks are subject to greater volatility. The indices representing each asset class are S&P 500® Index (large-cap stocks); CRSP6-8 Index (small-cap stocks) through 1978, Russell 2000 thereafter; Ibbotson Intermediate U.S. Government Bond Index (bonds); and Ibbotson U.S. 30-day Treasury bills (cash investments). For illustrative purposes only. Indices are unmanaged, do not incur fees or expenses, and cannot be invested indirectly. For additional information, please see schwab.com/indexdefinitions. Inflation is represented by the change in the Consumer Price Index for AII Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Timing the market is technically and, more often than not, emotionally difficult. But if you have money and savings that you don't need soon, staying invested in stocks and other investments tends to have more potential to earn a higher return over time.

Also, keep in mind that you should revisit your portfolio and evaluate your plan regularly (annually is a good place to start). Your plans and risk tolerance might change due to any number of extenuating circumstances, and portfolios need to be rebalanced as allocations to any asset class—stocks, bonds, and cash among them—can get out of sync with your plan and goals over time.

Bottom line: Cash isn't always the better course

There are plenty of good reasons to keep some of your hard-earned savings in cash and cash investments. But make sure that, based on your goals, you're not holding too much—especially because you're wary of volatility in investments in the short-term. Holding outsize cash positions can reduce long-term earnings potential.

This is particularly relevant in the case of younger investors, who likely have plenty of time to make up for market downturns before they need to tap their savings. And it's also true of those approaching retirement, who might be able to pad their retirement savings by reducing their cash balances.

Clients who aren't investing their money in assets with higher earning potential—especially after a number of years of strong market performance—often do so out of fear to commit to investments they perceive as unaffordable and the threat that a market correction is underway or imminent.

The best defense against making emotional investment decisions is to invest in a disciplined way. Based on when you need the money, save and invest each month in a diversified basket of investments with the potential to grow with the U.S. and global economy over time. How you split your assets between stocks, bonds, cash, and other asset classes can change as conditions or the timing of your needs warrant.

But the key is to maintain at least some exposure to all of them, keeping in mind your goals and time horizon. Holding too much cash might seem like the safe course at times, but you might find it costs you more in the long run.