Trading Options in Retirement

When investors think of strategies for retirement accounts, options are not always top-of-mind. But used effectively, options can be a great way to hedge and generate income. While there are a number of option strategies that can be employed in an IRA account, in this article I'd like to focus specifically on the three strategies listed below, since they're the most common and can be beneficial when used appropriately. Of course, these strategies can also be used in a taxable account.

Three strategies to consider

- Strategy

- Risk Level

- Strategy Type

- Complexity

-

StrategyBuy/Write (Covered Calls)Risk LevelMediumStrategy TypeIncomeComplexityLow

-

StrategyCollarRisk LevelLowStrategy TypeHedgeComplexityMedium

-

StrategyCash-Secured Equity PutsRisk LevelMediumStrategy TypeIncomeComplexityLow

Covered calls (long stock, short calls in equal quantity)

This is one of the most common options strategies. Consider entering a covered call if you have a neutral to slightly bullish sentiment. Covered calls can be a great way to generate income and provide a partial hedge in a flat or mildly up-trending market. While the risk protection is limited to the premium received, it may be enough to offset modest price swings on the underlying equity (or ETF, since they trade in the same manner as equity options).

You can sell covered calls at the same time a long equity position is purchased (buy/write), or on an existing equity position in your account (cover/write), usually after the position has already moved in your favor. While selling covered calls does create an obligation to sell the stock at the strike price which limits the upside potential of the underlying stock position, the income generated provides limited downside protection by effectively lowering the breakeven price of the equity position.

When you're establishing a covered call position, it's generally best to sell options with a strike price greater than the price you paid for the equity. If the stock remains flat, declines in value, or even increases a small amount, out-of-the-money calls will likely expire worthless and you'll keep the premium you received when you sold the calls. If that happens, you can sell more covered calls on the same equity position, for a subsequent expiration month.

If the stock appreciates above the strike price by the expiration of the option, your stock will likely be called away. This could occur prior to or at expiration. This is not necessarily a bad thing. If you sold out-of-the-money calls at a strike price at or above your cost basis, you will generally make a profit on both the stock and the options if assigned.

Let's look at an example:

Assume you buy 1,000 shares of XYZ stock at $72 and sell 10 XYZ Apr 75 calls at $2.00. The 2 points you receive for the covered calls provides 2 points of immediate downside protection. In other words, you won't start losing money until the stock drops below $70. Of course, there is always a downside and, in this example, the trade-off is that you limit the upside profit potential beyond $75. You would only want to do this if you thought the price of XYZ would not exceed $75 by the April expiration. If XYZ did increase above $75, the stock purchase alone would have been more profitable.

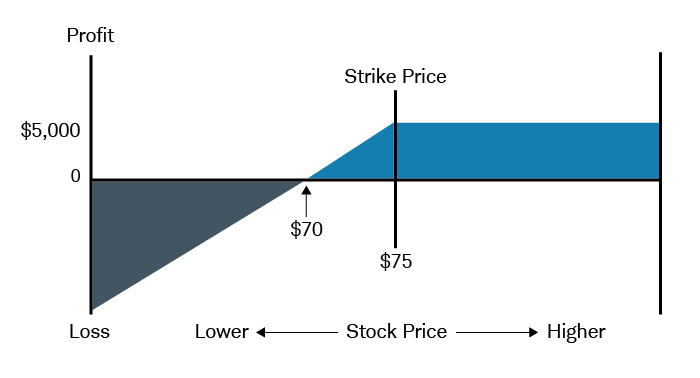

Viewing this strategy graphically, you can see that the breakeven price is $70 and the profit is capped at $5,000 for all prices beyond $75. Though the stock can drop 2 points before you go into the red, losses will be incurred below $70, and increase all the way down to zero. The losses will always be $2,000 less than the loss on the stock trade alone, but could be as much as $70,000 if the stock drops to zero, compared to $72,000 if you had simply bought the stock.

Covered call

Chart depicts strategy at expiration.

It is generally best not to sell a covered call option if your stock position has already moved significantly against you. Doing so could obligate you to a selling price that ensures a loss. To avoid locking in a losing trade, before you sell a covered call, always ask yourself the question, "Would I be happy if I had to close out my stock position at the strike price on this option?" If you can answer yes to this question, you will probably be okay.

Remember, if your stock rises in price and your covered call goes in-the-money, you can be assigned at any time. This is especially common on the day right before the ex-dividend date and any time during the week the option is due to expire.

Collars (long stock, long puts and short calls in equal quantity)

Consider establishing a collar if you are primarily concerned with protecting a position at minimal expense. A collar provides temporary protection against a downturn in the equity or ETF position, but also removes most of the upside potential. Since it's generally unwise to hold a long stock position if you think the long-term prospects are poor, you should only consider employing this strategy if you are concerned in the short-term, but feel the long-term prospects of your stock are still favorable.

Probably the biggest benefit of trading a collar is that it can often be done for little or no out-of-pocket expense; the proceeds received from the sale of the covered calls can be used to finance some or all of the purchase cost of the protective puts. In some instances, you may even be able to receive a small net credit. Unlike many other option strategies, collars generally don't get more expensive as you go further out into the future.

Since collars are best structured so that both the puts and the calls are out-of-the-money but have the same expiration date, the ideal situation is for the stock to increase just slightly (but not beyond the strike price of the call) after the collar is established. This will result in both the put and call options expiring worthless and a small gain on the stock.

Let's look at an example:

Assume you purchased 1,000 shares of XYZ at $52, and now the stock has risen to $72. You may still be optimistic about the long-term prospects of the company so you would prefer not to sell your position but in the near-term, perhaps you are worried about the next earnings report. Since you have a 20-point unrealized gain in this stock, lets also assume that you would be willing to risk a 2-point downward move, but you want to be protected against anything greater.

A protective put could provide the downside protection you seek, but if there were no downward move, the premium you paid would be lost. A covered call could provide limited downside protection and even generate a little income, but you could still lose all of your gains if the stock dropped substantially in price. A stop order below the current price might work, but if the stock gapped down before market open, you might not be protected, or you could have larger losses than you expected, and you might end up selling your stock. If your primary concern is just to hold steady without spending a lot of money, without selling your stock, and without the risk of substantial loss, a collar may be a good approach.

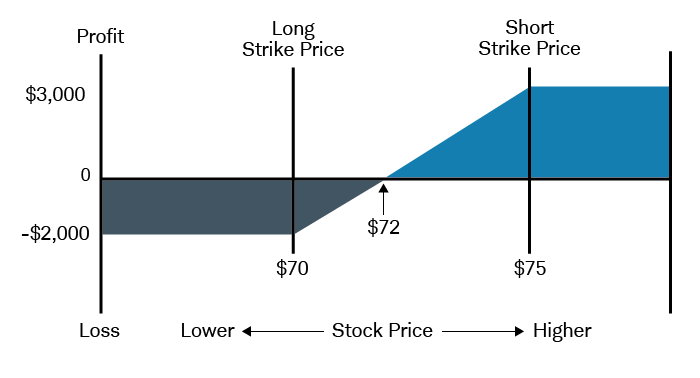

Assume you establish a collar by selling 10 XYZ 75 calls at 2.00 and purchasing 10 XYZ 70 puts at 2.00. Your total out-of-pocket expense would be only the commissions charged by your broker. Viewing all three positions graphically, you can see that the breakeven price at expiration is 72 (the current stock price). If the stock drops to 70 or below, you will not lose more than $2,000; if the stock increases beyond 75, you will not gain more than an additional $3,000.

If the stock drops below 70, to avoid having your put options automatically exercised, you could sell the puts at their market value before expiration. The proceeds from the puts should offset all but 2 points of the loss on the stock; but you would still incur a loss. If the stock rises above 75, to prevent the assignment on your calls, you could buy your short calls back at the market price before expiration. You would probably lose money on the call options and the loss would likely eliminate all but 3 points of the gains on the stock, but you would still have a net gain.

Collar

Chart depicts strategy at expiration.

A nice feature of a collar is that you can define the timeframe without greatly affecting the cost. You may decide to establish a new collar each month using options that expire in 30 days or less. As long as you can do the trades at even money or a slight credit, this strategy is beneficial because it may allow the stock to gradually scale upward in price, increasing your unrealized profit. Doing this repeatedly also takes the most effort, because you have to avoid getting assigned early and you have to adjust your strike prices each month. In the previous example, one of the potential outcomes was that the stock could end up above the strike price of the calls at expiration. If you were able to buy (to close) the calls without being assigned, you would probably end up with close to a 3-point net gain on the stock. In this scenario, you might consider a new collar by selling calls with a strike of 80 and buying puts with a strike of 75. This would allow for additional upside potential in the next month.

If you opted for a longer-term collar initially (perhaps using options that expire in six months), maintaining the position over that time would take less effort, but you might also miss out on further upside gains. Even if you go further out and establish the collar at a net credit, you would lock in a maximum gain of no more than about 3 points for six full months.

Remember, any time you purchase a (protective) long put option, you have the right, but not the obligation, to exercise your puts and sell your stock position at the strike price. If you choose not to exercise an in-the-money option, you will generally have the ability to close out that option by selling it in the market prior to expiration. Keep in mind that, since long options lose time value as expiration approaches, your options may lose value, even if the price of the stock remains stable. Likewise, if your short (covered) call option goes in-the-money, you could be assigned at any time. And since early assignments often happen on the day before the ex-dividend date, you'll also lose the next dividend payment.

Cash-secured equity puts or CSEPs (any number of short put options)

This strategy is similar to an uncovered (naked) put, except that with a cash-secured equity put (CSEP) you deposit the total amount of the potential assignment with your broker, in the event the put expires in-the-money and the stock shares are "put" to you. This ensures that you will be neither forced to purchase more shares than your deposit affords, nor lose money that you don't have; the put is "secured" by cash.

Consider establishing a CSEP if you are neutral or slightly bearish in the short-term, but bullish on the underlying stock or ETF in the long-term. Since a significant drop in the price of the underlying stock would likely result in you being forced to purchase the stock at a price above the market price at that time, you generally would not want to establish a CSEP if you felt the stock might drop significantly below the strike price on the put. Before selling a CSEP, you should always ask yourself the question, "Would I be happy if I had to buy the underlying stock at the strike price on this option?" If you can answer yes to this question, you will probably be okay.

When you sell a CSEP instead of immediately buying the stock, you may be able to purchase shares of stock below the current market price. This will happen if the stock drops sufficiently in price to cause the put to expire in-the-money and be assigned. If the stock does not make a short-term downturn, you will miss out on owning the stock, but you will still make a small profit on the put option.

Let's look at an example:

Assume you like the long-term prospects of XYZ and are therefore interested in buying 1,000 shares. You think $72 is a fair price, but you are concerned that it may take a small dip in the short-term. You could certainly enter a limit order at a price of $70, but instead you decide to sell 10 XYZ 70 puts at $2.00. To do so, you will need to deposit $68,000 with your broker, or have this much already available in your account. This is the difference between the potential assignment obligation of $70,000 and the $2,000 you will bring in on the sale of the puts.

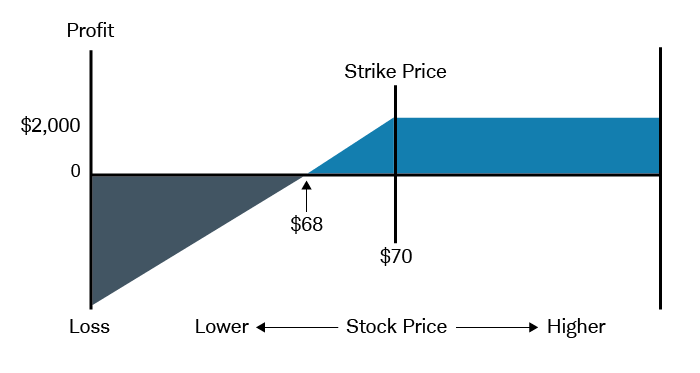

If the stock drops below $70 at expiration, you will be assigned 1,000 shares at $70. You should not be unhappy, since you have just bought a stock for $70, which you were originally considering at $72. Even better, your net cost basis is actually $68. Think of this like getting paid to enter a limit order. If the stock stays above $70, the puts will expire worthless and you will keep the $2,000 you brought in on the option trade, with no further obligation.

Viewing the CSEP strategy graphically, you can see that the breakeven price is $68, but the profit is capped at $2,000 for all prices above $70. Notice that, even though you will have 2 points of downside price protection, losses will still be incurred and increase below 68, all the way down to zero.

CSEP

Chart depicts strategy at expiration.

If the stock rises above $74, you will miss an opportunity to have had a larger gain, but you will still profit. If the stock drops below $68, you will begin to lose money but your losses will always be $2,000 less than if you had used a limit order and purchased the stock outright at $70. Under all circumstances, you will either make a profit or lose less money than if you had simply bought the stock. Remember, if your put option is in-the-money, you could be assigned at any time.

I've tried to cover the basic characteristics of covered calls, collars and CSEPs, but it's not possible to discuss everything. My examples did not include commissions or other expenses, which should be considered prior to any trade. Please consult your tax advisor about the tax implications of these strategies, especially if you use them in a taxable account.