Wall Street Jargon: 7 Market Cliches

When Wall Street speaks, anyone listening gets a pass if it sounds like babble.

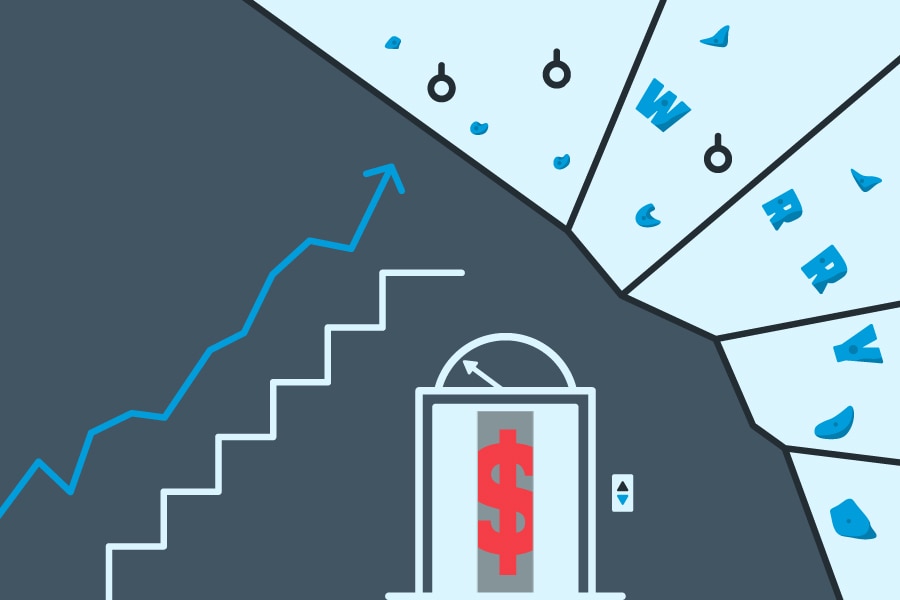

Some days, markets climb a "wall of worry." On other days, they may be "taking the stairs up"—that is, until the elevator doors open for an express return to ground level. And of course, remember not to try to catch a "falling knife."

Colorful adages and expressions have long been entrenched in market vernacular, and investors tuning in to financial media on any given day stand a good chance of hearing or reading select Wall Street cliches. Wall Street slang provides handy soundbites and helps distill complicated financial market subjects into a widely understood language. But what does Wall Street jargon really tell us about the markets?

There's truth behind every Wall Street cliché, but investors shouldn't just take these sayings at face value. It's a good idea for investors to define these terms, ask questions, and seek deeper insights that could help inform long-term strategy and decisions.

With that in mind, here's a primer on seven common Wall Street catchphrases.

1. Buy the rumor, sell the news

Nobody knows for sure what the future holds. But that doesn't mean traders and investors won't place trades hoping for a certain outcome.

Stock prices often move in a certain way ahead of earnings reports, mergers and acquisitions, and other events. Once the event happens, stock prices may reverse direction. For example, traders may buy shares of XYZ Corp. a week or so before the company is scheduled to report quarterly results, expecting XYZ to beat analysts' earnings estimates. When earnings day arrives, the company does indeed beat earnings estimates, but the share price falls. Why?

Sometimes a price decline reflects traders taking profits on gains they accumulated in the run-up to earnings or some other event. When the event happens, the strong earnings have already been "baked in" to the current price, and the stock requires further bullish news to move higher. Such short-term "buy rumor/sell news" trading tactics can be risky and may not be appropriate for long-term investors.

2. The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent

This oft-cited quote, or versions of it, is attributed to famous economist John Maynard Keynes. The message here is that no one is bigger than the market, and no matter how right you think you are about a certain stock or trend, the market doesn't care. The market does what it does, and it's the ultimate decider.

"Don't fight the [ticker] tape" is another old stock market term with similar meaning.

The irrational-solvent debate or talking point is sometimes brought up in the context of historic market bubbles—real estate or dot-com stocks, for example. Bubbles can inflate for many years as asset prices rise well beyond what's justified by underlying fundamentals and “irrational exuberance" often takes hold. For investors, rational decisions are one key to staying solvent and meeting long-term goals.

3. Never catch a falling knife

If a stock or market appears to be in free fall, it's not a good time to show off your outfield skills. The "falling knife" stock market term refers to a sharp price drop, and the message for investors is to basically get out of the way and don't get cut—it’s better to wait until the price appears to have bottomed before you consider buying.

Even then, proceed carefully. Just because a stock has stopped falling for the time being doesn't mean there's no more downside. "Bottom-picking" can also be risky. Plus, a falling-knife environment might signal or characterize a bear market, so investors should also be able to recognize bear markets and try to avoid bear market "traps."

4. Markets climb a "wall of worry"

Bull markets, or uptrending markets, are sometimes said to be climbing a "wall of worry," meaning stock prices are rising despite economic uncertainty, seemingly negative news, or a lack of positive news.

Coined in the 1950s, this expression "depicts a sustained stock market rise during a time of economic or financial stress," wrote veteran wealth manager John Nicola. "This sometimes also results from a herd mentality of investors who "buy on bad news."

A market posting consistent gains, even if current events don't look all that rosy, might be a sign of sustainable, underlying, long-term confidence or strength. Still, investors should be wary about getting lulled into complacency. Investors don't have to become full-time "worrywarts," but they can keep their eyes open for potential red flags, such as a spike higher in the Cboe Volatility Index® (VIX), often called the "fear gauge."

Other handy tools, such as Treasury prices and yields, can help monitor market sentiment. Valuation metrics like price-earnings ratios can help provide a sense of whether stocks are getting expensive or cheap.

5. Sell in may, go away

Following this logic, investors might consider unloading stock holdings ahead of the summer, which according to some researchers has been a historically weak period for the equity market; it's also a time when trading volume sometimes slows and volatility can increase.

There's also the notion that portfolio managers who outperformed the broader market during the first four or five months or so of the year may opt to sell some stocks and lock in gains, figuring they may only have to shadow benchmarks, such as the S&P 500® index (SPX), the rest of the year to meet their targets. ("Sell in May" is one of several seasonal axioms, along with the "Santa Claus rally.")

Still, this Wall Street term has earned ample skepticism. In recent years, markets have experienced some strong summer performances. In 2020, the SPX jumped 15% from the end of May through August. Also, it's unusual for investors to take a long-term vacation from the markets and their portfolio strategy at any time of year.

6. More buyers than sellers (or more sellers than buyers)

Free markets, by definition, require a willing buyer for every willing seller and a willing seller for every willing buyer, so on the surface, this stock market term seems like nonsense. But there may be a little insight deeper down.

Someone who says there are "more buyers than sellers" may be describing a market with high demand for or high interest in certain stocks. This may lead to greater numbers of buy orders coming in, which would likely push prices higher because investors and traders are willing to pay more and more for assets. Bull markets are characterized by increasing demand for assets and rising prices over time.

Conversely, if there are more sellers than buyers, prices may be falling rapidly amid stepped-up selling interest or a greater number of sell orders, perhaps triggered by an outside event like an earnings disappointment.

7. Stocks take the stairs up and the elevator down

Bull markets and long-term uptrends often unfold gradually over many years, reflecting (in part) broader, slow-moving economic and business cycles. In contrast, market downturns often happen much faster, sometimes in steep slides covering just weeks, days, or even minutes. Other times, a bubble "bursts" or a market "crashes" as fear takes over and selling cascades.

For example, the U.S. bull market that began in March 2009 and ended in early 2020 was the longest in history. But the end came quickly and dramatically when the S&P 500 dropped 34% in less than five weeks in February and March as the escalating pandemic roiled markets worldwide.

The final message? Maybe it's that all those veteran traders and investors "say" a lot of things. But the markets have the final word.