Box Spreads: What They Are and How to Use Them

Not every options strategy is designed to help traders speculate on the direction of the market or hedge their portfolios. Some more advanced strategies seek to profit from time decay (theta), shifts in volatility, or even the difference in how the market is pricing options relative to each other.

Short and long box spreads fall into this camp. These advanced options strategies allow traders to lend or borrow money synthetically at potentially favorable implied interest rates, making them powerful cash management tools.

Box spreads are complex and require precision to execute correctly, so it's important traders understand how these strategies work in practice—and the potential risks involved—before placing a trade.

What is a box spread?

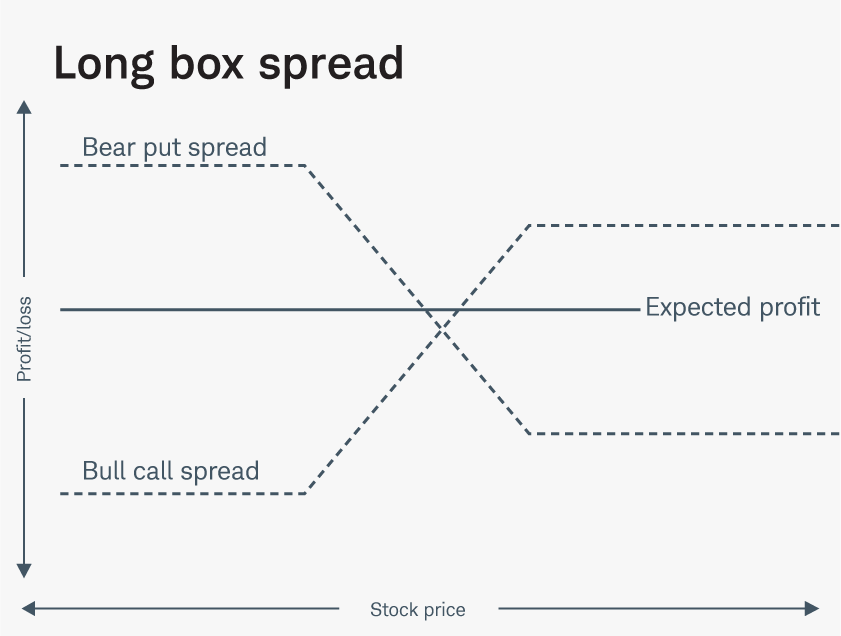

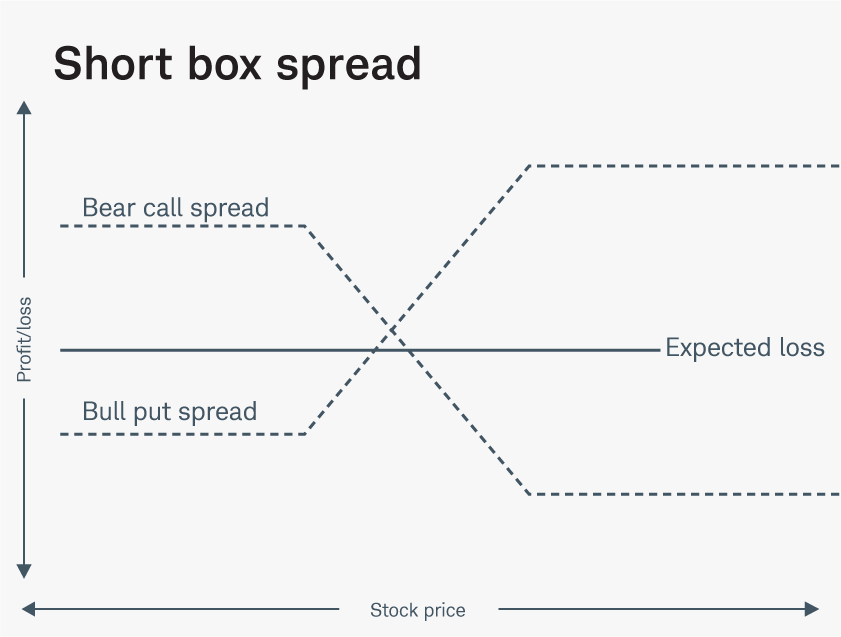

Box spreads are advanced options strategies that combine one bullish and one bearish spread. This structure—when executed correctly—removes directional bias, meaning the underlying security can theoretically move either way without affecting the strategy's outcome. By combining a bullish and bearish spread, a trader also defines the potential profit or loss at the outset of the trade.

Although some view box spreads as arbitrage strategies, they're more commonly used in practice by experienced traders and institutions to manage cash. Given the efficient pricing of today's options market—particularly for index options that are commonly used with these strategies—true arbitrage opportunities are rare, so the primary goal is simply to lend or borrow money through a synthetic method.

There are two types of box spreads: long and short.

What is a long box spread?

A long box spread combines a bull call spread and a bear put spread, allowing traders to lend money synthetically for a small, predetermined return. This return represents the implied interest rate earned by the trader over the life of the trade. To execute a long box spread, a trader would enter the following positions:

Bull call spread:

- Buy an in-the-money (ITM) call

- Sell an out-of-the money (OTM) call

Bear put spread:

- Buy an ITM put

- Sell an OTM put

In this strategy, all options share the same expiration date. Additionally, the strike prices for the bull call spread and the bear put spread must match. Because the trader is buying ITM options and selling OTM ones, the four-legged spread is opened at a net debit.

The profit for a long box spread is equal to the difference between the higher and lower strike prices minus the initial net debit paid to enter the trade (not including commissions, fees, and taxes). This payoff is fixed once the trader opens the position, assuming all legs of the trade are held through expiration by using European-style options. Using American-style options in a box spread can introduce early assignment risk (more on this later).

What is a short box spread?

A short box spread combines a bear call spread and a bull put spread, allowing traders to borrow money synthetically for a small, predetermined loss at expiration. This loss represents the implied interest rate paid by the trader. To execute a short box spread, a trader would enter the following positions:

Bear call spread:

- Sell an ITM call

- Buy an OTM call

Bull put spread:

- Sell an ITM put

- Buy an OTM put

All options must share the same expiration date, and the strike prices for the bull put spread and the bear call spread must match. The trader opens this spread at a net credit because ITM options are sold.

Under normal conditions, a short box spread produces a small guaranteed loss when executed correctly. However, the purpose of the trade is not to profit from the options themselves but to raise money temporarily that the trader may use elsewhere.

Risk profiles of short and long box spreads

When do traders use box spreads?

Some traders mainly use box spreads when the implied interest rate from the options market is perceived to be better than what they could receive from traditional lending or borrowing.

A long box spread might make sense when the synthetic lending return is higher than the interest rate on low-risk investments, such as Treasurys or Certificates of Deposit (CDs). On the other hand, a trader could use a short box spread when the implied borrowing rate is lower than the interest rate available from other financing options like margin or bank loans.

Beyond rate comparisons, traders often use box spreads to manage cash that's already in their trading accounts. A long box spread might earn a small return on uninvested cash, while a short box spread can temporarily raise cash for other trades.

Box spread risks

Some traders refer to short and long box spreads as "riskless" because they are neutral strategies that aim for a set profit or loss at expiration when executed correctly. However, this is a misconception. As with any trade, there are risks involved with box spreads—particularly when using American-style options.

Consider the following non-exhaustive list:

- Early exercise risk. When executing a short box spread using American-style options, an early assignment on one of the short legs can effectively unravel the strategy. This exposes traders to interest rate risk, dividend risk, hard-to-borrow risk, and potentially significant losses that could trigger a margin call. Traders trying to avoid early exercise risk can do so by using European-style options, which can only be exercised on the expiration date.

- Liquidity and execution risk. Box spreads involve four separate options contracts, and less liquid markets can make it harder to fill these orders at the expected prices. If some or all four legs can't be filled at the intended prices, the small fixed profit on a long box spread can be lower or even turn into a loss, while the small fixed loss on a short box spread can increase.

- Tax implications. Profits and losses from box spreads on certain cash-settled index options are generally subject to IRS Section 1256 rules. This means net gains or losses are marked to market each year under the 60/40 rule, with 60% treated as long-term capital gains and 40% as short-term capital gains. Some traders see this as a benefit, but the IRS can reclassify certain trades, potentially leading to less favorable tax treatment. Overall, the tax treatment of box spreads is complex because it varies depending on the underlying asset and how the trader implements the strategy. Traders should consult a tax professional for further guidance.

- Marking considerations. Due to how exchanges, clearing houses, and brokerages mark options, establishing their current value, box spreads can sometimes cause an account to show losses, restricting other opportunities for traders due to a reduced net liquidation value. Liquidity issues can make marking all four legs of box spreads at the desired prices particularly difficult for brokerages and exchanges. This may lead box spreads to trade over- or undervalue, especially during volatile periods when bid/ask spreads widen.

Example of a short box spread

A trader wants to secure a synthetic loan using options for a five-month period. On October 16, 2025, they decide they'll do this by executing a short box spread on the cash-settled, market-capitalization-weighted S&P 500® index (SPX).

With SPX trading at $6,632, the trader executes a bear call spread and a bull put spread, both expiring on March 20, 2026, creating their short box spread in the following way:

Bear call spread:

- Sell 1 SPX 6,600-strike call (ITM)

- Buy 1 SPX 6,700- strike call (OTM)

Bull put spread:

- Sell 1 SPX 6,700-strike put (ITM)

- Buy 1 SPX 6,600-strike put (OTM)

The trade's result—as shown below using the thinkorswim® paperMoney® platform—is a credit to the trader's account of $9,830 (excluding commissions, taxes, and fees). This credit is the sum of the premium received from the short call and short put minus the sum of the premium paid for the long call and long put.

Source: thinkorswim platform

At expiration, the trade will settle to a net cash outlay of $10,000, or the value of the 100-point difference between the higher and lower strikes, regardless of where SPX is trading at expiration.

Subtracting the initial credit received of $9,830 from this buy-back cost, the trader would have effectively received a five-month loan of $9,830 for a net cost of $170 (excluding commissions and fees). This $170 is the implied interest the trader pays for their synthetic loan.

To illustrate how the box structure of this strategy makes the price of SPX at expiration irrelevant to the outcome, let's break down three examples.

1. If SPX declines and is trading at $6,500 at expiration:

- Short call at $6,600 expires worthless.

- Long call at $6,700 expires worthless.

- Short put at $6,700 loses $200.

- Long put at $6,600 gains $100.

The result is a loss of $100. Multiplying that by the number of shares in the contract (100), the trade would settle for $10,000 at expiration.

2. If SPX is basically flat, trading at $6,650 at expiration:

- Short call at $6,600 loses $50.

- Long call at $6,700 expires worthless.

- Short put at $6,700 loses $50.

- Long put at $6,600 expires worthless.

The result is, again, a loss of $100, obligating the trader to outlay a total of $10,000 at settlement.

3. If SPX gains and is trading at $6,800 at expiration:

- Short call at $6,600 loses $200.

- Long call at $6,700 gains $100.

- Short put at $6,700 expires worthless.

- Long put at $6,600 expires worthless.

The result of this trade is also a loss of $100, obligating the trader to outlay a total of $10,000 at settlement.

In each scenario, regardless of the price of SPX, the trader will be required to outlay the $10,000 at expiration. Subtracting the initial credit received of $9,830, the trader is left with a net loss of $170, no matter how SPX moved. This is the implied interest paid for the loan.

A trader looking to quickly compare the implied interest rate paid for their synthetic loan to other potential loan sources would use the formula Rate = Interest/(Principal x Time), where principal equals $9,830, interest equals $170, and time equals 5 months divided by 12 months. Their calculation would be:

Rate = $170/(9,830 x 5/12)

Rate = 0.0415

Multiplying this rate by 100 to convert it to a percentage would mean the trader paid a 4.15% annualized implied interest rate for a $9,830 synthetic loan over a roughly five-month period, excluding commissions, taxes, and fees.

Note: The "time" in this calculation is a rough approximation, the "principal" is equal to the initial credit received, and the "interest" is equal to the implied interest paid.

Box spreads: A cash management tool

Box spreads show how traders may use advanced options strategies for more than just hedging or speculation—they can also be an effective tool to help manage cash. Traders can earn a small, yield-like return on cash already in their trading accounts with long box spreads, or they can raise cash to trade or invest over a set period with short box spreads.

However, both strategies should only be executed by advanced traders who understand the mechanics and risks involved. Because of their complexity, even minor errors in execution can lead to unexpected losses.