What Are Options Collars?

Down markets can cause dramatic portfolio swings, especially when large percentages are tied up in a few stocks. Traders can help prepare for inevitable bearish or even range-bound periods through hedging strategies that temporarily shield stock prices from larger-than-expected price drops or frustrating periods of sideways price action. One low-cost way of doing this—for traders familiar with options strategies—is with an options collar. While not an uncommon strategy, the way a collar is implemented can vary from one investor to the next. Some investors may turn to the collar options strategy when they want to hedge unrealized profits; others are focused purely on avoiding downside risk.

Just like other options strategies, an options collar can be implemented on individual equities and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), assuming there are listed options on the underlying. It's important to note the liquidity of each underlying to assess whether a strategy is a good fit. Those looking to implement options collars for protection would typically want to see relatively narrow bid/ask spreads and healthy volume and open interest in the options before establishing any position, even for a hedge.

Options collars: The basics

In addition to a long stock position, a collar consists of two options with the same expiration: a long out-of-the-money (OTM) put and a short OTM call. The collar's long put acts as a hedge for the long stock (potentially limiting its downside losses), and the premium collected by selling the short call helps finance the cost of the long put (remember, it's possible to lose 100% of funds invested in the long position). Another way of thinking of this strategy is the combination of a covered call1 and a protective put.2

Like all our strategy discussions, the following is strictly for educational purposes only. It is not, and should not be, considered individualized advice or a recommendation. Options trading involves unique risks and is not suitable for all investors. Collars and other multiple-leg options strategies can entail substantial transaction costs, which may impact any potential return.

Step 1: Buying a protective put

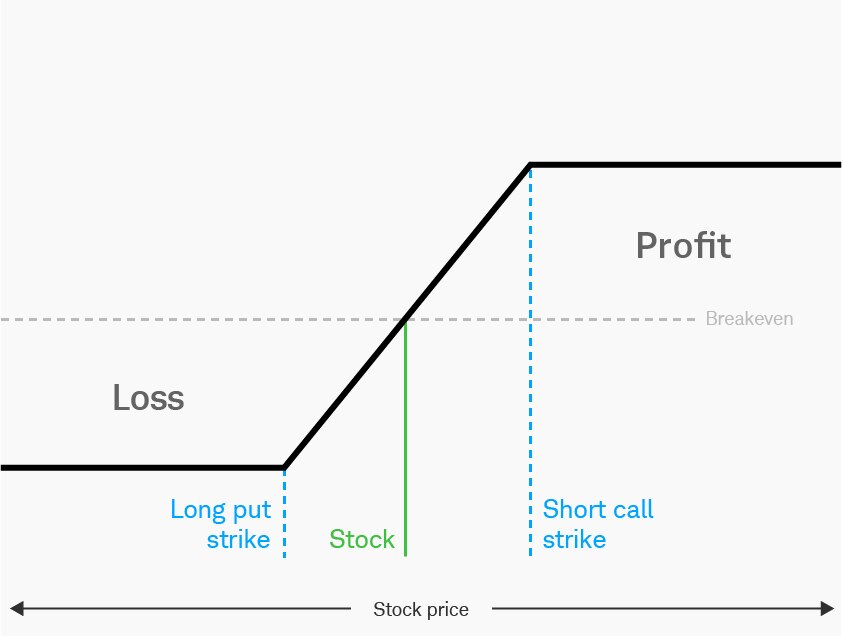

The options collar risk profile shows the strategy's limited risks and limited returns. For illustrative purposes only.

Long put options are not just for bearish traders. Buying puts can also be used by bullish traders looking for a measure of short-term protection against a drop in the underlying's price. This protection kicks in at the strike price, which is important to keep in mind when selecting which option to buy. But the higher the put strike, the higher the premium.

Example:

- Stock ZYX is currently trading at $90

- OTM 86-strike put is purchased for $1 per contract

- The protective put trade's potential loss is limited to $5—the $4 difference between the stock price and strike price, plus the $1 paid for the option (plus transaction costs)

Step 2: Selling a covered call

While the cost of a protective put may not seem excessive relative to the stock price, buying this hedge month after month (if a trader chooses to) can add up. That's especially true if the implied volatility rises, suggesting the market is anticipating the stock to make large moves.

Selling an OTM call can help offset the cost of buying a put. Once all three pieces are in place (long stock, long OTM put, and short OTM call), an options collar strategy is in place. If a trader gets the call to completely cover the cost of the put—as in the example above—this would be selling an OTM 95-strike call for $1, then the trader has what is known as a "zero-cost" collar.

Just as the put limits risk if the stock price drops below the put strike, the short call caps the potential profit on the stock. Essentially, the put creates a "floor" beneath the stock and the call acts as a "ceiling." The trader's choice of strike prices—where to place the floor and the ceiling—determines the trade's overall risk and reward.

An options collar's potential results

The collar's max loss occurs if the stock price is below the strike price of the long put at expiration. At that point, the trader might choose to exit the stock position by exercising the put, selling the put in the open market, and letting the call expire worthless. If it's before expiration and the trader wants to exit the stock by exercising the put, they'd likely want to close the call first due to the potential risks of holding a short call without the stock.

The max profit occurs if the stock price is above the strike price of the short call at expiration because the shares will be sold at the strike price when the short call is likely assigned and the put expires worthless. The options collar risk profile below shows the limited risks and returns of the collar strategy. Keep in mind, this is theoretically what should happen. However, carrying options positions into expiration can entail additional risks; for example, an unanticipated exercise/assignment event could occur or an anticipated event may fail to occur.

Deep pockets help

Traditionally, an option trader might place a collar over their long stock, and let it expire without adjusting it. But the nature of collars gives them flexibility, not only when putting the collar on, but also as time passes and the stock price moves. In fact, larger investment managers use this flexibility to build a bigger stock position by using a strategy known as a "dynamic collar." The dynamic collar originated with institutional investors and money managers who were looking to establish large positions in a stock over time but wanted a hedge against market corrections.

Rolling options to higher strikes and further out in time accommodates a stock that is still trending up. If both options are still OTM as expiration nears, a trader may be able to roll both options into deferred-month contracts to keep some protection in place. And if the stock does indeed pull back below the put strike? The trader may be able to roll the put into another strike, or they could exercise their put, knowing the loss was limited.

An options collar's potential risks

While the options collar strategy can be effective in either a volatile or range-bound market, like many options strategies, it has some serious risks that need to be considered.

Early assignment: The covered call could theoretically be assigned before the trader had the chance to close it out or roll out to the next expiration. Should this happen, the trader would lose their stock or ETF position and could face tax consequences. Assignment usually only happens when the call option goes in the money, but that's not always the case. While early assignment can occur at any time, it's most likely to occur the day before the ex-dividend date or during the week of expiration.

Tax complications: This strategy can generally be used in an individual retirement account (IRA) or other tax-deferred accounts without any problems. However, if you're using it in a taxable account, you should seek professional tax advice because several complications could arise:

- Income earned on the collar will typically be taxed at your ordinary income rate.

- Be sure that both the call and the put options are OTM when establishing the collar, or a trader could run afoul of the IRS rules. These can be complicated, and the trader may not be able to deduct losses from their stock or ETF until they close the full position.

- If a trader hasn't held the underlying position for 12 months (qualifying for long-term capital gains treatment), establishing a collar could freeze or reset the holding period of the ETF position.

- If the stock goes ex-dividend when the collar is in place, the dividend may not qualify for the 15% long-term rate.

- If the underlying position is closed out at a loss (whether through assignment or sale), the IRS wash sale rules will disallow the loss if a trader buys the stock or ETF back again within 30 days.

- For more information on the tax rules regarding options, consider reading the following publication: IRS Publication 550: Investment Income and Expenses and seek the advice of a tax professional.

Bottom line

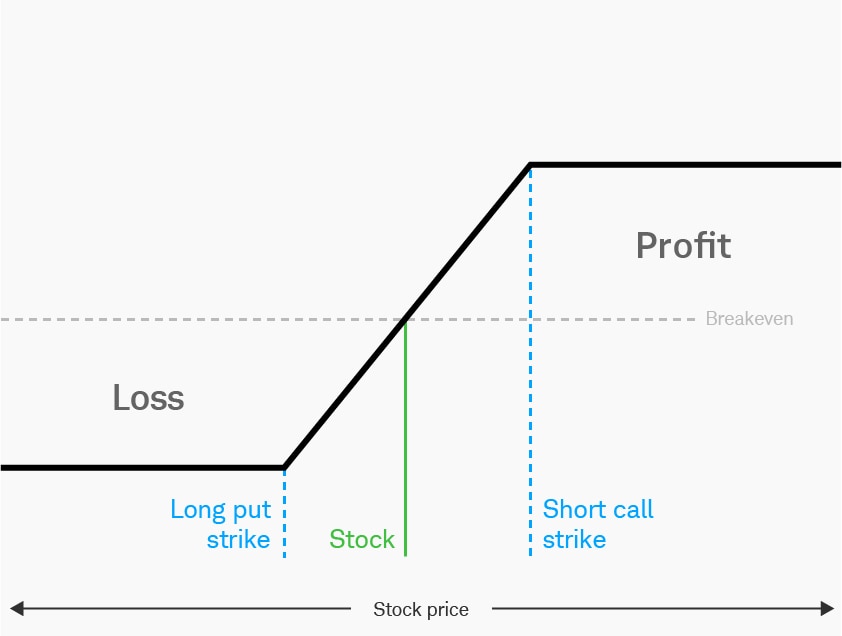

For illustrative purposes only.

The goal of an options collar is to earn short-term income that can partially or fully offset declines in the value of the stock or ETF positions. It's a popular strategy for traders who still maintain a bullish outlook on the underlying stock or ETF but are nervous about upcoming sideways or declining price action.

The collar options strategy may not be particularly tax-efficient, nor is it a strategy for inexperienced option traders. Because this strategy requires active management and close monitoring, traders should consider first experimenting via a paper-trading platform before committing real funds.

Are options collar strategies for you?

What if the investor doesn't buy 1,000 shares of stock? Are 100 shares more appropriate for the investor's account. Do dynamic collars still make sense? That question would need to be evaluated by each investor.

In a scenario where the stock price drops and an investor uses the profit from a long put and short call to buy more shares, the profit might not be enough to buy 100 shares. Although it's possible to trade odd lots (less than 100 shares) of stock, there could be a mismatch between the options position's contract size and the number of shares.

For example, if the profits from a collar composed of 100 stock shares, long one put, and short one call are enough to buy 10 shares of stock, the position will have 110 shares. But each standard equity stock option has a deliverable of 100 shares per contract. There aren't standard equity options with a deliverable of 110 shares. One long put and one short call hedge only 100 shares. But two long puts and two short calls might be too much of a hedge.

Collar vs. long call spread

A long call vertical spread is a less capital-intensive strategy that has risks and rewards similar to the collar (see the risk graph above). However, in the absence of long stock, a way to make the call vertical dynamic is with delta. How many positive delta does the long call vertical have, and how many delta does the trader want when the stock price drops?

Using our 48/52 collar example with the stock at $50, the synthetically similar call vertical would simply be long one 48 call and short one 52 call with a delta of +20. No stock and no put here.

Now, suppose the stock price immediately drops to $48, and the 48/52 call vertical loses $40. The collar could also lose the same $40, but that would be made up of, hypothetically, a $200 loss on the stock and a $160 profit on the long 48 put and short 52 call. After closing the collar, the investor could use the $160 to buy three shares of stock at $48 (not including transaction fees). But instead of buying three shares, the long call spread's delta may increase by a little more than 3%, which is similar to adding three shares to a 100-share position.

Like the dynamic collar, trading long verticals in this way can result in additional transaction fees.

And that's how some investors build a bigger position without spending extra capital. Although dynamic collars may be more geared for active traders and require a fundamental grasp of delta that may seem complex at first, it's worth taking a close look at the strategy, as well as the less capital-intensive vertical call spread, that the pros have been running with for years.