7 Good Ideas for New Investors

Starting to invest might feel intimidating if you feel like you have to figure everything out on your own—but, fortunately, there are plenty of good examples to follow. Successful investors tend to share similar tendencies about when and how to invest. Here's a look at seven ideas to get you going.

1. Earlier is easier

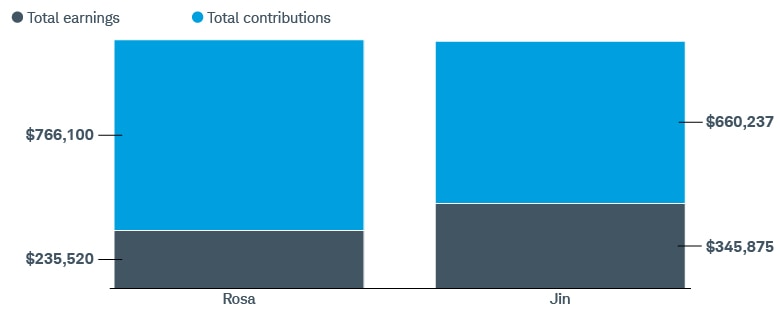

The earlier you start investing, the less you may need to save to reach your goal, thanks to the potential for long-term compound growth. Consider two investors who start with an initial investment of $1,000 and want to save $1 million by age 65:

- Rosa starts investing at age 25, so she needs to save just $5,720 a year to achieve her goal.

- Jin, on the other hand, doesn't start investing until he is 35, so he needs to save $11,125 a year to achieve the same goal.

At age 35, Jin still has three decades to invest to meet his goal, but he has to save nearly 50% more to achieve the same goal as Rosa. Not everyone will be able to do that, which is why it's so important to invest as much as you can as early as you can.

Save early, save less, earn more

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Calculations assume an initial investment of $1,000, a lump-sum investment on January 1 of each year, and a 6% average annual return and do not reflect the effects of investment fees or taxes. The example shown is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent actual investment performance.

Hypothetical performance is no guarantee of future results.

2. Diversify, diversify, diversify

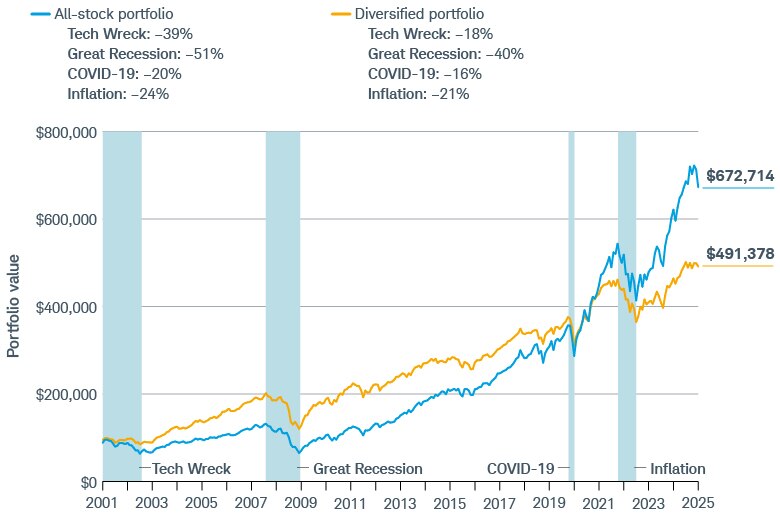

You can help protect your portfolio against large drops in the market and also potentially boost your portfolio's value through diversification.

For example, if you had an all-stock portfolio, you could invest in large-cap, small-cap, and international companies. You could further diversify your holdings by investing in different sectors, such as technology and health care. Finally, within the technology sector for example, you could buy stock in hardware, software, semiconductors, and networking. For new investors, exchange-traded funds and mutual funds are an easy way to diversify without doing a lot of research on individual investments.

Alternatively, if you're interested in particular companies, fractional shares can be a sensible way to diversify your large-cap stocks in the S&P 500®. Because you're not purchasing a whole share, fractional shares are more affordable, allowing you to practice your trading skills while potentially risking less money.

Keep in mind that stock prices can fall as quickly as they rise, depending on market conditions and other economic factors. If you're not willing—or able—to handle such volatility, a portfolio comprising stocks, bonds, and other asset classes could mitigate your risk over the long haul, especially during a bear market.

A diversified portfolio can help minimize losses during a downturn, and when your portfolio is less volatile, you won't be as likely to make rash decisions that could undercut your savings.

Diversifying can lower risk

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research, with data provided by Morningstar, Inc.

Time period examined is from 03/31/2001 to 03/31/2025. Stocks are represented by total annual returns of the S&P 500® Index. The diversified portfolio is a hypothetical portfolio consisting of 18% S&P 500, 10% Russell 2000, 3% S&P U.S. REIT, 12% MSCI EAFE, 8% MSCI EAFE Small Cap, 8% MSCI EM, 2% S&P Global Ex-U.S. REIT, 1% Bloomberg U.S. Treasury 3–7 Yr, 1% Bloomberg US Agency, 6% Bloomberg US Securitized, 2% Bloomberg U.S. Credit, 4% Bloomberg Global Agg Ex-USD, 9% Bloomberg VLI High Yield, 6% Bloomberg EM Aggregate, 2% S&P GCSI Precious Metals, 1% S&P GSCI Energy, 1% S&P GSCI Industrial Metals, 1% S&P GSCI Agricultural, 5% Bloomberg U.S. Short Treasury 1–3 Mo. Including fees and expenses in the diversified portfolio would lower returns. The portfolios are rebalanced annually. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent a specific investment product. The example assumes a starting portfolio balance of $100,000. Total returns include reinvestment of dividends, interest, and other cash flows. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses, and cannot be invested in directly. All drops are calculated using monthly values. Diversification and asset allocation strategies do not ensure a profit and cannot protect against losses in a declining market. Investing involves risk, including loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Though we don't recommend it, if you're comfortable with risk, you could reach your financial goals with a diversified all-stock portfolio. Instead, it would be wiser to consider including other assets in your portfolio, especially if a volatile market causes you heartburn.

Transcript of the podcast:

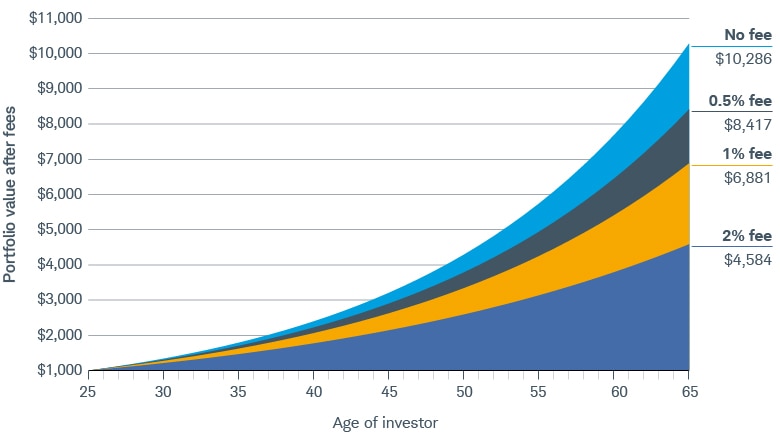

3. Small fees can make a big dent over time

Management fees—from expense ratios charged by mutual and exchange-traded funds to the annual advisor fees—are often a necessary part of investing. That said, even seemingly small differences can erode your returns over time.

Make sure you're getting what you pay for—whether that's strong returns, exceptional service, emotional support that keeps you on track, or practical, trustworthy advice. In any case, it's wise to scrutinize your investment expenses regularly—perhaps as part of your annual portfolio review.

Low fees can result in greater returns

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Ending portfolio balances assume a starting balance of $1,000 at age 25 and represent the amount contributed and the earnings compounded annually. The example assumes a hypothetical average rate of return of 6%, reinvestment of dividends and capital gains, and no current taxes paid on earnings. This hypothetical example is only for illustrative purposes.

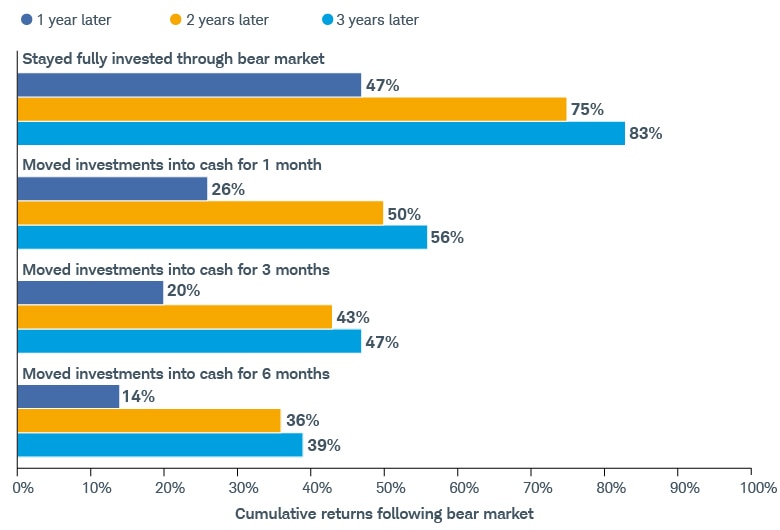

4. Once invested, stay invested

When the market is in a free fall, you might be tempted to flee to the safety of cash. However, pulling out of the market for even a month during a downturn could seriously stunt your returns in the long run.

For example, let's say we experience a bear market, where the market declines 20% or more. To avoid further losses, you sell your riskier assets and invest in cash until the market improves. But timing the market is difficult to predict, and the longer you wait to get back in, the less opportunity you have for potential growth.

Holding firm can pay off

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research, with data from Morningstar, Inc.

The market is represented by the S&P 500® TR Index, using data from 01/01/1970 to 03/31/2025. Cash is represented by the total returns of the Ibbotson U.S. 30-day Treasury Bill Index. Total return includes the reinvestment of dividends, interest, and other cash flows. Since 1970, there have been a total of seven periods where the market dropped by 20% or more. The cumulative returns are calculated as the simple average of the cumulative return from each period and scenario. Cumulative return is the total change in the investment price over a set time. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent a specific investment product. Example assumes an investor switched to cash investments in the month the market reached its lowest point and remained in cash for either one, three, or six months before reinvesting in stock. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses, and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The problem with selling during a market drop is that by the time you act, the worst may already be behind you. Not only could you be locking in your losses, but you're likely to miss some of the best days of the recovery, which often happen within the first few months of a decline.

5. Planning can help lower your tax bill

The goal of investing is to make money, and when you do, Uncle Sam will come for his share. But there's still plenty you can do to try to minimize your tax hit. For example, how you sell appreciated investments can have a big impact on how much of your capital gains you get to keep.

You never want to think about taxes after the fact because, by then, it's too late. Instead, taxes should be an integral part of your investment choices—seemingly small decisions can have big implications on your tax bill.

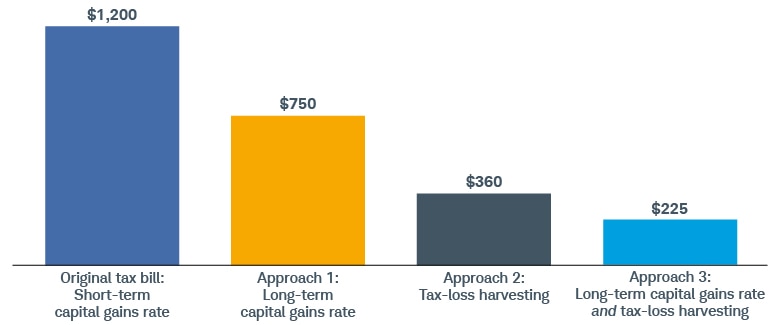

Let's say you're a single filer with an annual salary of $150,000. You're considering selling stock that you've held for 11 months, which would result in a $5,000 gain. Because you've held the investment less than a year, your earnings will be taxed at your marginal federal tax rate of 24% —leaving you with a $1,200 tax bill ($5,000 × 0.24). Take a look at how you can lower your taxes on your capital gains.

Pay less, keep more

To reduce your taxes, you could take one of three common approaches:

- Approach 1: Hang on to the investment for at least a year and a day so your gains will be taxed at your long-term capital gains rate of 15%. (Long-term capital gains rates are 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on income, plus a 3.8% surtax for certain high-income earners.) Waiting to sell your investment would reduce your tax liability to $750 ($5,000 × 0.15), but be aware that your investment could decrease in value during that time.

- Approach 2: Sell another investment at a loss to offset some or all of your gain, a process known as tax-loss harvesting. For example, if you realize $3,500 in losses, your gains would be lowered to just $1,500, and you would owe $360 ($1,500 × 0.24).

- Approach 3: Combine approaches 1 and 2—holding on to your investment for at least another month and a day and realizing $3,500 in losses to offset your $5,000 gain, resulting in a $225 tax bill ($1,500 × 0.15).

This hypothetical example is only for illustrative purposes.

6. Saving has a place in an investing strategy

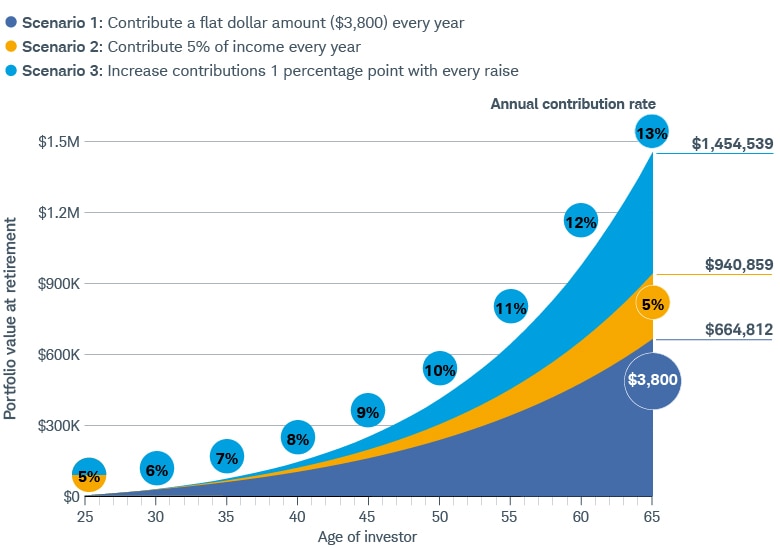

Smart investors contribute regularly to their portfolios. Think of these contributions as saving for your future, and how you save can make a noticeable difference to your portfolio over time. When you're new to investing, contributing a flat dollar amount each year can be simple, but is it the best way to save?

Instead, consider depositing a percentage of your income so your contributions increase anytime your income does. This approach doesn't eat into your take-home pay because it's being skimmed off your raise, and it's harder to miss what you never had to begin with. Indeed, increasing the percentage by at least a point anytime you get a raise can have an even greater impact on your portfolio value.

Here's how these three saving strategies compare after 40 years of investing.

Invest your savings

A 25-year-old starts investing with $3,800, which is 5% of their annual salary of $76,000. For the next 40 years, the investor can continue contributing $3,800 each year, increase the amount to 5% of their income as it changes, or increase the percentage 1 percentage point every year they receive a raise.

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research.

In Scenario 1, the investor contributes 5% of their pretax income in the first year and then contributes that same dollar figure in subsequent years. In Scenario 2, the investor contributes 5% annually at the start of every year from age 25 through age 65. In Scenario 3, the investor contributes 5% annually at the start of every year beginning at 25 and then increases the contribution rate by 1 percentage point with each raise. Scenarios assume a starting salary of $76,000, annual cost-of-living increases of 2%, and a 5% raise every five years. Ending portfolio balances assume a 6% average annual return and do not reflect the effects of investment fees or taxes. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent a specific investment product.

One of the easiest—and most obvious—ways to start saving and investing when you're young is through a workplace retirement plan, such as a 401(k), offered by many companies. Some employers will even match your contribution up to a certain point, so it's wise to take advantage if possible—not contributing enough to earn the match is like turning down free money. It's an easy way to boost your savings, helping you generate more wealth over the long-term.

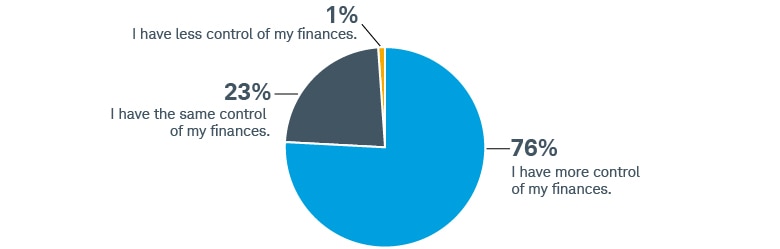

7. Putting financial goals in writing makes them tangible

Seeing your goals on paper makes it easier to envision your financial future, which can motivate and guide you along the way. Schwab's 2024 Modern Wealth Survey found that 96% of individuals who have a written plan are confident they'll reach their financial goals.

To plan or not to plan

People who put in the effort to plan for the future feel more in control of their finances and are more likely to take the steps necessary to make that vision a reality.

Source: Schwab Modern Wealth Survey.

The online survey was conducted by Logica Research from 03/04/2024 to 03/18/2024, among a national sample of 1,000 Americans aged 21 to 75. An additional 200 Generation Z Americans completed the study. Quotas were set to balance the national sample on key demographic variables.

Your investment strategy should begin with a well-thought-out plan—then try implementing just a couple of these ideas and see how your financial journey progresses. You can always make adjustments along the way. Here's to your future!